During his exceptionally long life (1749-1832) Goethe formed many friendships. Not all were lasting, and some are puzzling. One that seems incongruous is his friendship, over some ten years, with the Zurich clergyman Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801).

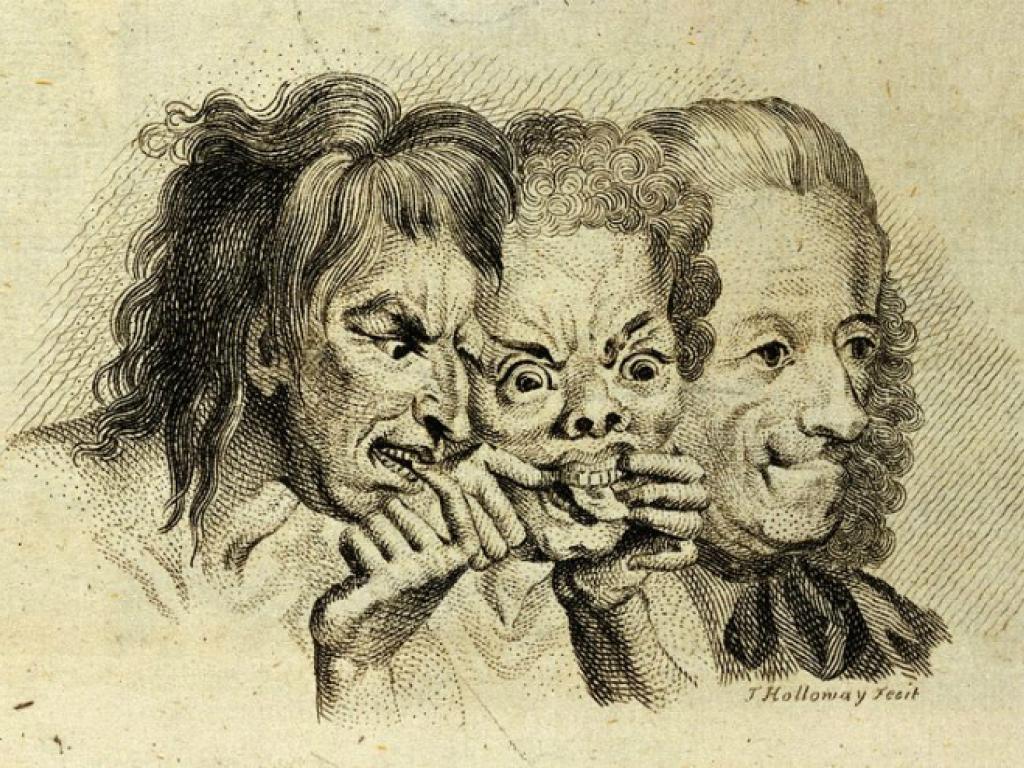

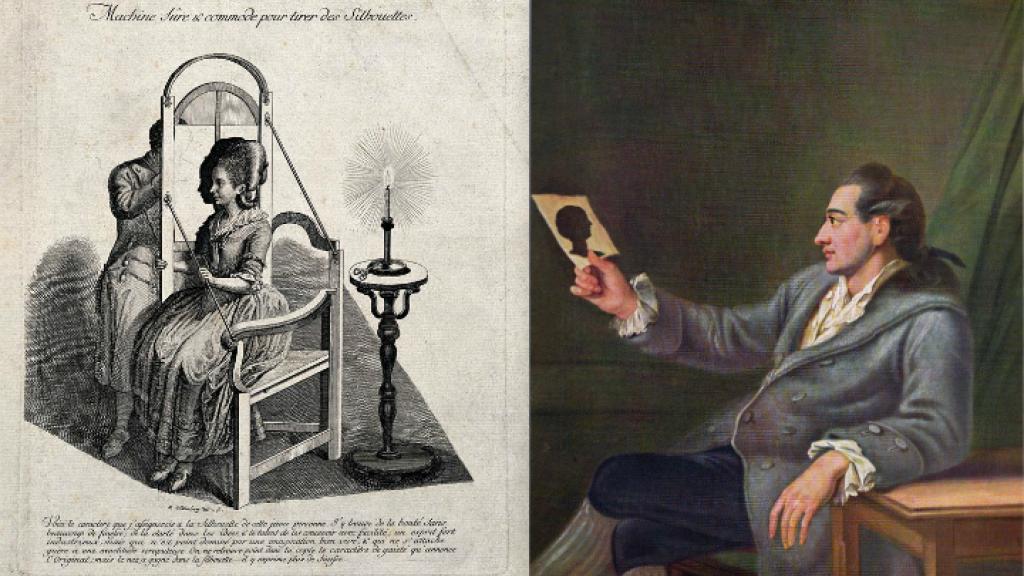

Lavater is now remembered, if at all, for his amply illustrated books on physiognomy (which Goethe helped him to publish). He believed that people's moral character could be inferred in precise detail from their facial features. But he was also an enthusiastic and idiosyncratic Christian evangelist. He took literally the passage in St Mark's Gospel (16:17-18) where Jesus tells his disciples that in his name they will be able to speak in tongues, cast out devils, and heal the sick. According to Lavater, such powers were latent in all Christians, who by developing them could acquire a Christ-like nature. Lavater was on the look-out for gifted people in whom such powers were near the surface, and thought he had found one in Goethe.

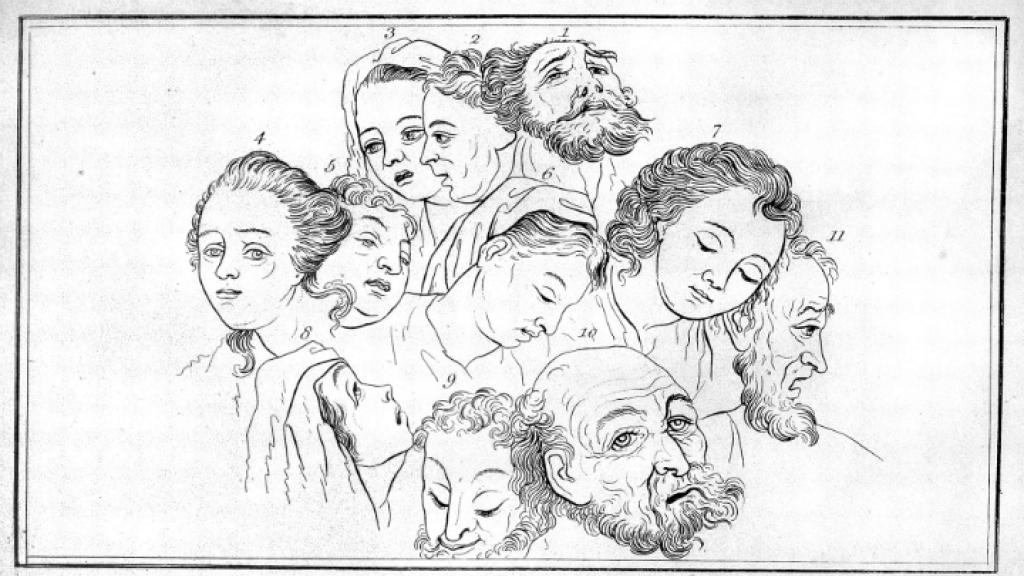

From Essays on Physiognomy (1789-1798) by Johann Caspar Lavater.

Goethe for his part was blunt with Lavater, telling him in a letter of 1773: 'I am not a Christian'. He had already reviewed sceptically the third volume of Lavater's Aussichten in die Ewigkeit (Prospects of Eternity), a treatise describing heaven and hell in prosaically material terms. They met for the first time in summer 1774, when Lavater made a long trip down the Rhine. To his surprise, Goethe liked Lavater immensely, finding him warm, genuine, enthusiastic, and 'his soul full of the heartiest love and innocence' (letter to G. F. E. Schönborn, June 1st – July 4th, 1774). Goethe liked people who were distinct individuals – who felt real – and Lavater was certainly that.

In the early 1780s, however, their friendship cooled. Goethe tired of Lavater's importunate evangelizing. He vented his irritation by telling Lavater that he was 'a decided non-Christian', and also privately in a poem:

'You are! You are!' says Lavater. 'You are!

You are! You are! You are, Lord Jesus Christ!'

He wouldn't keep uttering words and doctrine so vehemently

If there weren't something fishy about the matter.

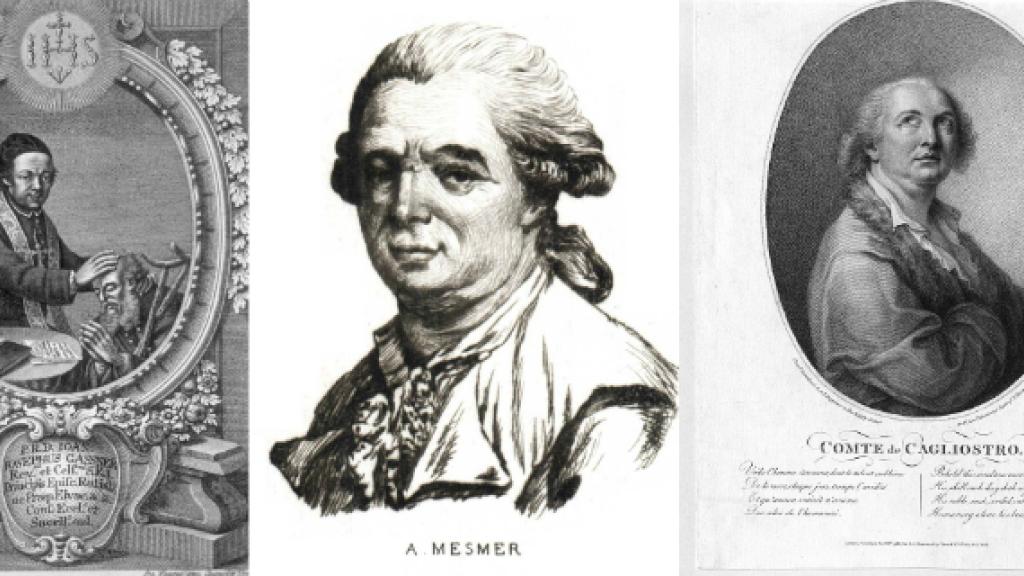

Goethe could not share Lavater's fascination with the numerous faith-healers who appeared in the 1780s: the popular exorcist Gassner, the hypnotist Mesmer, and the notorious impostor Cagliostro. Lavater met all three, and found them disappointing. Goethe acknowledged Cagliostro's gifts, but distrusted him from the outset, ridiculed his claim to be an Egyptian priest, and caricatured him in the drama The Great Cophta. So Lavater seemed absurdly gullible.

Left to right: Johann Joseph Gassner (unattributed), Franz Anton Mesmer (unattributed), and Giuseppe Balsamo Cagliostro (R. S. Marcuard after F. Bartolozzi, 1786).

Moreover, around 1780 Goethe was devoting himself to the serious study of nature. His interest in mineralogy produced the essay 'On Granite' (1784), and his work in anatomy enabled him to discover the intermaxillary bone, connecting the upper and lower jaws, which had not previously been known to exist in the human body. Although this discovery has since been questioned, it confirmed for Goethe the value of studying the world that was solidly real. In 1786, after watching sea-snails and crabs in the Venetian lagoon, he reflected: 'how delightful and magnificent a living thing is! How exactly matched to its condition, how true, how intensely being!' By comparison, Lavater's fantasies were empty, and his material heaven showed his lack of imagination.

How delightful and magnificent a living thing is! How exactly matched to its condition, how true, how intensely being!

The last straw came when Lavater published an epic poem about Nathanael, the disciple who spontaneously acknowledged Christ (John 1:49), and dedicated it 'To a Nathanael whose hour has not yet come'. Goethe was offended by the evident allusion to himself. Thereafter their relations ceased. On a visit to Zurich in 1797, Goethe spotted Lavater's tall, lanky figure in the distance, and changed direction to avoid meeting him.

Inscription: 'Lavater, Goethe, and Basedow at lunch in Koblenz' (1864).

What lay behind their relationship? Was it just that Goethe liked Lavater as a person while rejecting his beliefs and deploring his way of propagating them? No: Goethe liked Lavater not despite but because of his religious fervour. Goethe was fascinated not only by individuality but by charisma. He was drawn to magnetic personalities. For contemporaries, he was himself such a person, as is clear, for example, from the recollections of Goethe in the autobiography of another religious friend, Johann Heinrich Jung-Stilling.

But Goethe also knew that charisma was dangerous. Many prophets were false prophets. He depicted such figures in two comedies of the 1770s, Pater Brey ('Father Porridge') and Satyros, and planned a searching exploration of the psychology of the prophet Muhammad in a play that unfortunately consists only of a summary and two completed scenes. Later, Cagliostro proved to be a real-life false prophet.

Left to right: an engraving showing Lavater's Apparatus for Taking Silhouettes in action (1783); young Goethe with a silhouette portrait, by Georg Melchior Kraus (1775-76).

Goethe's relation to Lavater helps us define his relation to the Enlightenment. Generations of German scholars, following Germany's defeat of France in 1871, dismissed the Enlightenment as a shallowly rationalistic French import that could not take root among the naturally spiritual Germans. Now, thanks not least to the work of my predecessor T. J. Reed, it is possible to see the German classical age as integral to the Enlightenment, and the Enlightenment itself as promoting a conception of reason, or good sense, that goes far beyond the rationalism of earlier figures such as Descartes.

To Goethe, narrow rationalism, and its accompanying materialism, were a dangerous error. Following his understanding of Spinoza's pantheism, Goethe believed that reality was itself divine. He said of Spinoza: 'he doesn't prove the existence of God; existence is God’ (letter to F. H. Jacobi, June 9th, 1785). Christianity was unnecessary.

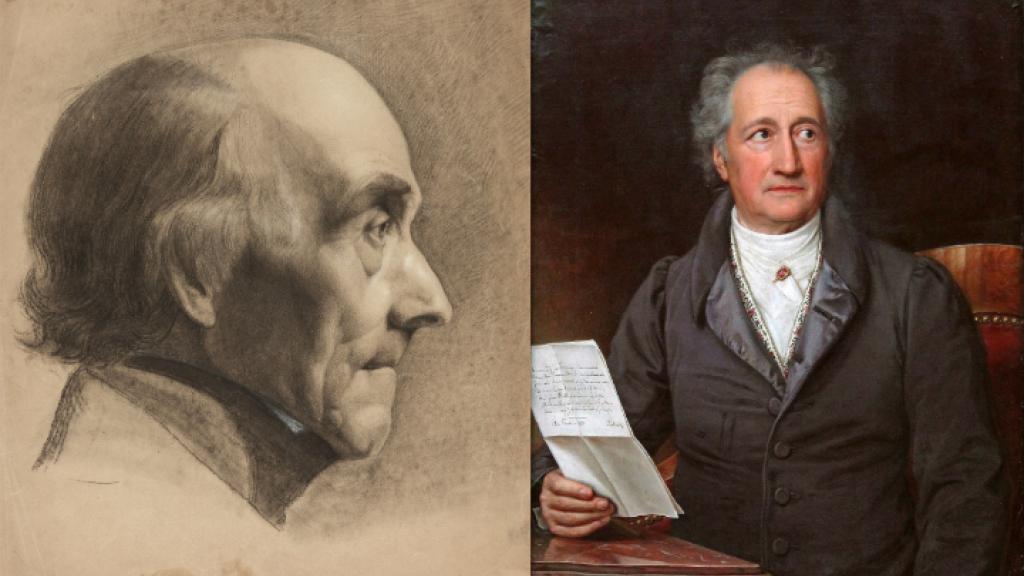

Left to right: Johann Caspar Lavater by Johann Heinrich Lips (before 1817); Johann Wolfgang von Goethe by Joseph Karl Stieler (1828).

In his poem 'Prometheus' Goethe attacked the Christian God in the guise of Zeus, and in his humanist play Iphigenie auf Tauris he showed the gods to be an antiquated and pernicious projection of human impulses. But rationalism was no alternative. In a famous passage of his autobiography, he denounced the materialism of the Paris Encyclopaedists, and he considered dry rationalism also to be the spirit of the Berlin Enlightenment, typified by the copious author Friedrich Nicolai.

[Spinoza] doesn't prove the existence of God; existence is God.

By contrast, Lavater's religious fervour at least tapped into a living spirit that was beyond the understanding of rationalism. But such fervour risked absurdity and credulity. It could also be abused. So Goethe turned his attention increasingly to the natural world, which was real, living, and divine. In doing so, he was developing the Enlightenment programme of empirical study. 'In natural phenomena,' wrote the French naturalist Buffon, 'nothing is well defined but what is accurately described; now in order to describe accurately, one must have seen, seen again, examined, compared the thing one wants to describe, and all this without prejudice, without preconceived ideas.'

Professor Ritchie Robertson

Taylor Professor of the German Language and Literature, MML

Fellow of The Queen’s College