I recently visited Buenos Aires to catch up on recent films, as part of my research and preparation for teaching a popular final-year option on contemporary Latin American cinema. One movie in particular stands out: Lucrecia Martel’s Zama. Martel (b. 1966) made her name with a series of works set in and around her native Salta in the Argentine north-west: subtle and closely observed studies of the local bourgeoisie in all their grotesquery. These early films, La Ciénaga, The Holy Girl and The Headless Woman disturb and provoke in a variety of ways, both psychologically and politically. Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian recently named her as one of his key directors of the 2000s.

Zama is a story of waiting.

Zama marks a break with what looks retrospectively like a self-contained trilogy. It is a historical drama, based on the novel of the same name by Antonio di Benedetto. The book, from the mid-1950s, anticipated the ambition of the 'boom' novels (of García Márquez, Cortázar, Vargas Llosa, et al.), with its fractured narrative, unreliable first-person narrator, and wide historical sweep. It was very much ahead of its time, but like other pre-boom novelists — Juan Rulfo, in particular, but also Arguedas, Bombal, and Onetti — has remained beloved of specialists and other writers, but little known to the wider world. A recent translation into English, championed by J. M. Coetzee in the New York Review of Books and Michael Wood in the LRB, as well as this film, may help di Benedetto towards the reputation he deserves.

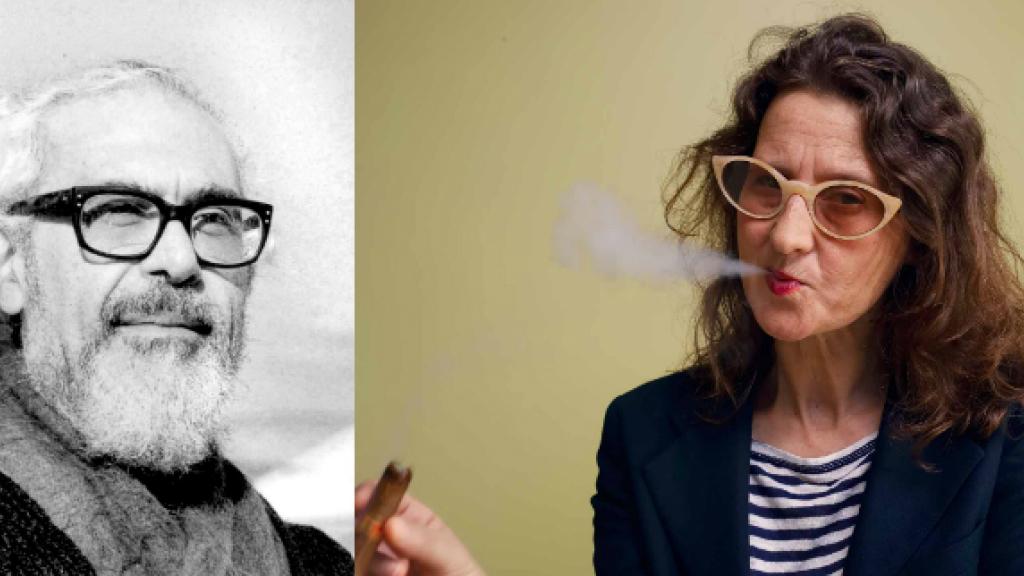

Left to right: Antonio di Benedetto; Lucrecia Martel by Domenico Stinellis & AP Images (Venice, August 31st, 2017).

Zama is a story of waiting. The titular protagonist — Don Diego de Zama — is a magistrate in the Spanish colonial administration, posted to a northern province in present-day Paraguay, away from the metropolis, and also from his wife and children in Buenos Aires. Martel sticks closely to the basic shape of di Benedetto's narrative, and maintains the focus on Zama. But she omits the helpful dates that allow the reader to understand that the three separate sections occur some years apart, at the end of the 1790s. A long beard, and a now ragged red frock-coat, in the final section, testify to years passed and Don Diego's decadence.

Martel shows the banality of colonial life, as well as the almost unnoticed everyday cruelties to slaves and indigenous. But the tone is never moralising, and the mood of many of the scenes is of light absurdity.

Zama (Daniel Giménez Cacho) made his reputation by efficiently stamping out indigenous uprisings and for his even-handed, minimally violent approach to discipline. But his heyday is now in the past. He is desperate to be transferred, partly to be reunited with his family, partly to escape the heat and humidity found upriver.

The first third details Zama's dalliance with a beautiful aristocratic Spanish woman, Luciana Piñares de Luenga, played by Lola Dueñas, who offers to shepherd Zama's career back to more favourable climes. Martel shows the banality of colonial life, as well as the almost unnoticed everyday cruelties to slaves and indigenous. But the tone is never moralising, and the mood of many of the scenes is of light absurdity. Zama then falls out with his underling, and they brawl in the royal offices. As a punishment, the junior man is exiled, back to Spain — a punishment Zama himself sorely craves.

Daniel Giménez Cacho as Don Diego de Zama. Zama by Lucrecia Martel (2017; Bananeira Filmes and Rei Cine).

The second section finds Zama with a son, born to an indigenous woman, and a new scribe, who is working on a book in his free moments in the office. The latter is a cause of outrage for the incoming Governor, and Zama is tasked with investigating and writing a merciless, damning report about the manuscript. Kafka did not invent tortuous bureaucracy, Martel's film seems to tell us.

Payment from the royal coffers fails to arrive, and financial penury forces Zama to move into a rotten, half-abandoned inn on the edge of the already precarious outpost. There he is troubled by illness and visions, and Martel does well to make sense of the mysterious and — deliberately — confusing hauntings in the middle of the book. The director captures the filth and deprivation of this environment, as well as the pettiness of a class system designed to hold it all in order, through appearances, protocol, and if necessary violence.

Lola Dueñas as Luciana Piñares de Luenga and a young boy. Zama by Lucrecia Martel (2017; from production stills).

There are humorous leitmotifs throughout: Zama staring intently at the river as if willing a boat to come; the messenger with a bright blue jacket, gleaming white wig, but without trousers, who delivers one or another unpleasant piece of news to the magistrate. Zama persuades the Governor, impressed by the report that condemns perhaps the only person in the settlement who truly admires and cares for him, to write to the King on his behalf. He is told that after the first letter, another in one or two years' time will certainly have some effect. A slight crack in Zama's impassive expression, in close up, tells us the breaking effect that this wait will have.

The film wears the influence [of Apocalypse Now] lightly, not exactly comic in register, but aware of the stupidity of it all.

The last section finds Don Diego, in a desperate bid to curry royal favour, joining a military party hunting a bandit, Vicuña Porto. The renegade was thought dead, but has reappeared, and Zama joins a military party to hunt him down. Led by a conceited Spanish captain, played with gruff swagger by Rafael Spregelburd, the party's mission is fruitless, even suicidal. Attacked by local tribes, ravaged by illness, and then crossed by a series of mutual betrayals, the men who haven't died or deserted fall into the hands of the bandit himself. This is Apocalypse Now territory, especially in the shape of the barely sane Vinuña Porto (a terrifying Matheus Nachtergaele), but the film otherwise wears the influence lightly, not exactly comic in register, but aware of the stupidity of it all. Zama meets a grisly end. The novel suggests possible salvation, but it is also redolent of a dying man’s hallucination. The film leaves both possibilities open.

Lucrecia Martel on the set of Zama, 2017 (from production stills).

Zama is an ambitious change of tack for Martel. Lushly shot, in particular its blue skies and worn-out colonial grandeur, exquisite in its period detail, and with a series of bravura central performances — its star, the Mexican actor Daniel Giménez Cacho in particular, his expression hardly ever wavering, yet full of sentiment and meaning — it deserves all its critical praise. I especially look forward to seeing what our undergraduates will make of it.

A version of this interview previously appeared in the Oxford Magazine. Our thanks for the permission to reproduce the material.

Professor Ben Bollig

Professor of Spanish American Literature, MML

Fellow and Tutor in Spanish at St Catherine's College

Associate Lecturer at St John's College