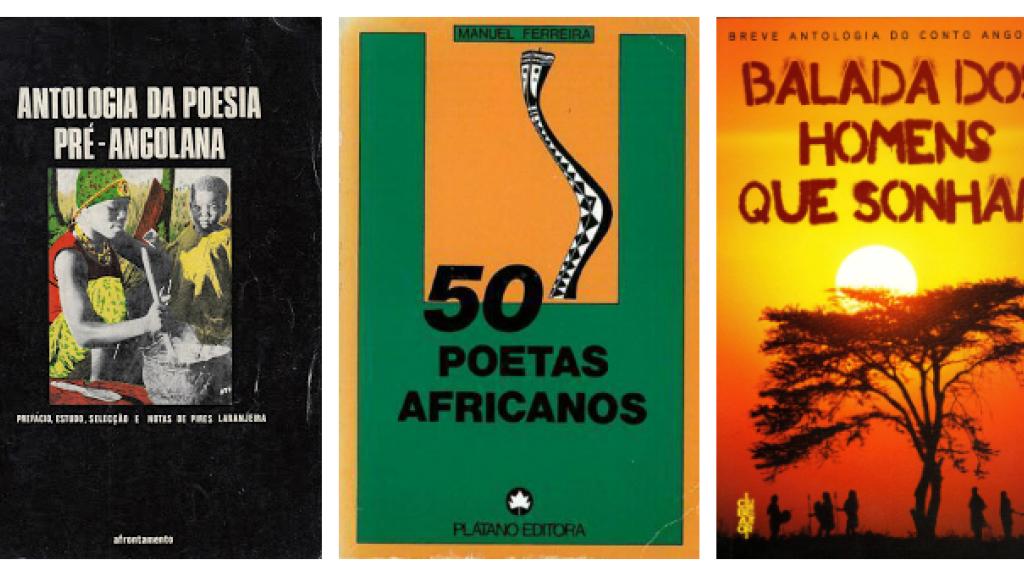

Women authors do not exist in Angola. That, at least, is the conclusion you would reach after reading the most seminal anthologies of Angolan writers. For example, no woman appears in Pires Laranjeira's collection of pre-independence Angolan poetry, Antologia da Poesia Pré-Angolana (1948-1974) (Porto: Afrontamento, 1976). Of the fifteen poets from Angola included in Manuel Ferreira's 50 Poetas Africanos (Lisboa: Plátano, 1989), not one is a woman. In Balada dos Homens que Sonham (Luanda: UAE, 2011), an anthology published by the Angolan Writers Union, all the authors are men.

These three collections from different moments in Angola's young history are symptomatic of a general trend that excludes female creativity from the Angolan canon. That trend reflects the challenging political environment women have faced since the nation's independence in 1975.

Anthologies of Angolan and African writing; left to right: Antologia da Poesia Pré-Angolana (1948-1974), 50 Poetas Africanos, and Balada dos Homens que Sonham.

In contrast to other former Portuguese colonies in Africa that have enjoyed female presidents (Guinea-Bissau), women prime ministers and foreign ministers (Mozambique and São Tomé e Príncipe), and women as chairs of the national assemblies (Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and São Tomé e Príncipe), Angola has historically lacked women in prominent political positions beyond presidential relatives. In the cultural sphere, despite being the wealthiest and most ethnically diverse of all the former Portuguese colonies, Angola lags far behind its lusophone counterparts in recognizing the legitimacy of women as writers who contribute to a national sense of self, and who merit a wide readership and a critically engaged reception.

Women authors do not exist in Angola.

My research seeks to address this by drawing attention to and analyzing the writings of Angolan women, from the 1940s to the present day. I read a range of women writers as exemplary challengers to the evolving patriarchies of their times. They were and continue to be voices that refuse to be silenced despite a cultural and political conspiracy to exclude their writings because of their sex. Their work bears reading alongside the rise and fall of an MPLA narrative of the Marxist 'New Man'.

Celebration of the results of Angolan presidential elections (2017), with the MPLA candidate João Lourenço securing the victory (by Stephen Eisenhammer for Reuters).

The MPLA (People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola) has ruled Angola since independence in 1975 with an ever-increasing degree of political dominance. From its inception in the 1950s, the MPLA placed culture — and in particular literature — at the heart of the nation-forging process. Its lack of recognition of women writers is a residue of the rhetoric of the independence struggle that put men at the heart of the Revolution, and women purposefully on the sidelines — relegating them to wombs at the service of the future.

Against that discouraging backdrop, a range of women writers has engaged with and distorted the very words that propagated the MPLA's sexist worldview. These women subversively echo, for example, the verses and speeches of Agostinho Neto, Angola's first president and national poet, and tackle the subtle chauvinism of Angola's most famous male writers including Pepetela and Manuel Rui. They recalibrate women as subjective cultural agents before, during and after independence.

Left to right: Lília da Fonseca, Alda Lara, and Deolinda Rodrigues.

Writers like Lília da Fonseca (1916-1991), Alda Lara (1930-1962), Deolinda Rodrigues (1939-1968), Chó do Guri (1959-2017), Ana Paula Tavares (b. 1952) and Antónia Domingos (b. 1970) offer us a very different view of what it means to be Angolan than their male counterparts.

[Women writers] were and continue to be voices that refuse to be silenced despite a cultural and political conspiracy to exclude their writings because of their sex.

Lília da Fonseca is considered to be Angola’s first woman writer. Her work can be read as a critique of colonial Angolan society and its male elites. The lasting value of Fonseca’s work lies in the relevance of her observations to postindependence gendered practice. Alda Lara wrote extensively about freedom and justice, as well as the place of motherhood in a more equitable society. Her work demonstrates a tension between the demands of being a mother and national liberation — a tension the male elites of Angola would later exploit to downgrade the position of women as political agents in their own right. Deolinda Rodrigues is celebrated as a heroine of the independence struggle, and her diaries and writings are often presented as a paradigm of female revolutionary virtue. Closer reading reveals her more ambivalent feelings about the position afforded to women in the new Angola for which she fought and died.

Left to right: Chó do Guri, Ana Paula Tavares (by Ivone Ralha), and Antónia Domingos.

Chó do Guri, Tavares and Domingos are examples of women who became culturally active in the aftermath of independence, and who are increasingly impatient with the limited agency assigned to women by the Angolan cultural establishment. Through poetry and prose, they foreground female embodiment, women's desires, and the stark limitations of an overly abstract hyper-masculine narrative of Angolan independence. They repeatedly challenge 'traditional' African stereotypes of women and the MPLA's ideologically loaded exclusion of female creativity.

The fundamental question guiding my current research is how women writers challenge the nationalist narrative of their moment, demonstrating through their work powerful instances of subversion that lay bare the gender-biased inconsistencies of a rhetoric of equality for all espoused by the MPLA and its cultural precursors. Their unique position stems not just from their femininity, but rather from the fact that the political system has marginalized them — giving them a perspective that speaks truth to power in unsettling ways.

Professor Phillip Rothwell

King John II Professor of Portuguese, MML

Director, European Humanities Research Centre