On 17 February 1943, a student at the University of Munich named Sophie Scholl was writing a letter to a friend. As she wrote, she listened to Schubert’s Trout Quintet on the gramophone. ‘[It] makes me want to be a trout myself’, she wrote. ‘You can positively feel and smell the breezes and scents and hear the birds and the whole of creation cry out for joy. And when the piano repeats the theme of cool, clear, sparkling water — oh, it is sheer enchantment.’ The following day, Sophie and her brother Hans were arrested while distributing anti-Nazi leaflets at the University of Munich. On 22 February, they were tried for treason along with Christoph Probst, another student. Hours later all three were executed by guillotine. Hans was 25, Christoph was 24, and Sophie was 21. They had been part of a resistance group known as Die Weiße Rose (The White Rose) which in the early 1940s printed and distributed six leaflets calling for resistance to Nazism and an end to the Second World War. Further trials followed as other members of the group were rounded up, among them students Willi Graf and Alexander Schmorell, and a university lecturer, Kurt Huber. The group’s last completed leaflet was smuggled out of Germany, and in the autumn of 1943 millions of copies were dropped over the country by Allied aircraft. The same year, the exiled German novelist Thomas Mann dedicated one of his regular BBC broadcasts to the White Rose, declaring: ‘Good, splendid young people! You shall not have died in vain; you shall not be forgotten. […] A new faith in freedom and honour is dawning.’ The war would roll on for another two years, but the White Rose would indeed not be forgotten.

2018 marks the 75th anniversary of the first White Rose trials, during which the core six members of the resistance group were executed. The White Rose Project commemorated this event with an exhibition, entitled ‘The White Rose: Reading, Writing, Resistance’, at the Taylorian Institution Library in October 2018. Much has been written about the White Rose since the first post-war account of their activities was published by one of the Scholl siblings, Inge, in 1952. Their letters and diaries, available in German and in English translation, give a fascinating insight into the lives of these young people who chose to stand up to the Nazis.

What motivated them to resist? After all, both Hans and Sophie Scholl had been enthusiastic members of the Hitler Youth in the 1930s. What made these young people’s attitudes shift? One answer to this persistent question lies in the fact that the members of the White Rose were voracious readers. Their letters and diaries make frequent mention of the books they were reading, and they sometimes read communally, reading passages aloud in turn, and discussing the ideas they encountered. Our exhibition makes the most of the Taylorian’s holdings, and where possible we have exhibited editions comparable or identical to those which the White Rose members read. Their reading was wide and enthusiastic: Dostoevsky, Bernanos, Mann, Rilke, Heine, to name but a very few authors. By looking at what they read, we also get a valuable glimpse into the character of these remarkable young people. While undertaking compulsory Labour Service (which she hated), Sophie commented rather disparagingly on some of the other girls who kept with them a copy of Goethe’s Faust in order, as she said, to give themselves airs. It should be said that during this period Sophie herself was alternating between Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Augustine’s Confessions, neither of which could be termed light reading.

Hans, on a 3-month tour of duty at the Russian Front in 1942, came firmly to reject Nazi assertions that the Russians were inferior through his encounters with ordinary people, and with their literary culture. He commented in his diary in August 1942: ‘We Germans don’t have Dostoyevsky or Gogol. Nor Pushkin nor Turgenev. What about Goethe and Schiller? someone retorts. Who does? A scholar. When did you last read Goethe? I don’t recall — in school or somewhere. I ask a Russian: What writers do you have? Oh, says the Russian, we have them all, all of them. […] What Russian is this? A peasant, a washerwoman, a mailman.’

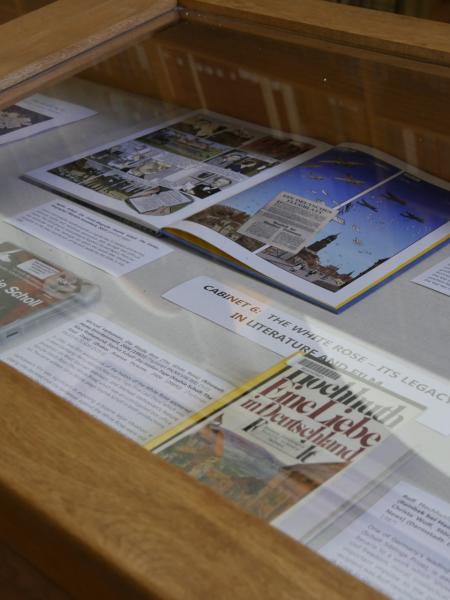

The exhibition focused on the way literature and philosophy shaped the group's thinking, as well as presenting information and artefacts relating to the Nazi book burnings, the White Rose leaflets, their legacy in literature and film, and historical examples of resistance through reading and writing. As part of the project, we are also commissioning a new translation of the White Rose leaflets to be undertaken by Oxford students. The leaflets are fascinating texts: they reflect the development of the group’s approach, the changing situation as the war progressed, and draw on a range of philosophical ideas and influences. They quote Goethe, Schiller, and Novalis, as well as the ancient Chinese philosopher Laozi and the Old Testament. The leaflets called on the German people to resist Nazism, to open their eyes to the atrocities being committed in the name of the regime, and to spread the word. As the fourth leaflet declares: ‘We will not be silent, we are your guilty conscience; the White Rose will give you no peace!’.

The members of the White Rose were extraordinary in what they did, but they were also quite ordinary students — they lived, loved, complained about their problems, made jokes, went out, drank, went to lectures and so on. Sophie was a remarkable individual, but she was also a relatable young woman. This is what Marc Rothemund attempted to show in his award-winning and popular 2005 film Sophie Scholl — Die letzten Tage (Sophie Scholl — The Final Days), which has done much to popularise the account beyond Germany.

The story of the White Rose is best told when the group members speak for themselves, in their private writings and in the leaflets, and not when they are idealized or mythologized. There has been criticism of their youthful impetuosity; some have questioned how much concrete change they achieved. Nevertheless, for those of us who work closely with young people, this history provides a moving and inspiring example of how it is possible to speak truth to power, and how conscience and moral courage can challenge injustice.