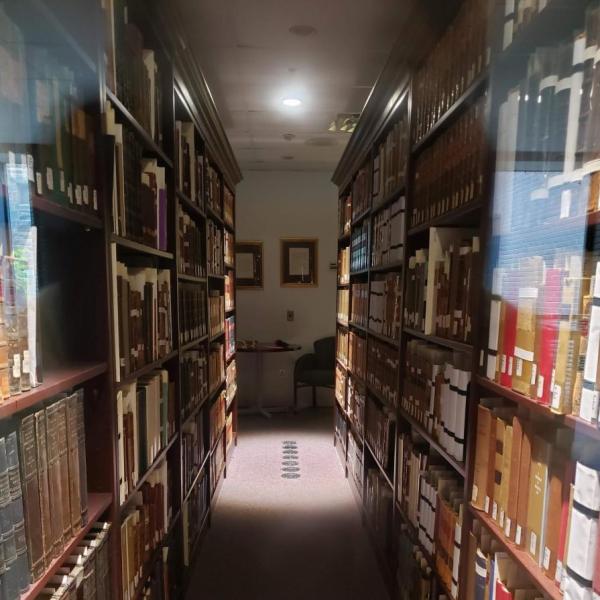

C’est un des grands trésors du patrimoine national français hors de l'Hexagone, au même titre que les impressionistes au Met! [1] exclaimed a startled legal history professor from Paris when he visited a collection of Old French law books in a secluded reading room in a university library in Montreal some years ago. A highlight of my year abroad in Quebec has been stumbling across a remarkable resource for scholars interested in Old French and Old French law. The Wainwright Rare Book Collection is hidden in corner of McGill University’s vast Law Library on the slopes of Mount Royal, overlooking the Montreal skyline.

Don’t worry, I haven’t spent the whole of my year abroad in Quebec holed up in a library. But a passion for old French literature from my work as an undergraduate at St. Peter’s College, combined with a feminist’s curiosity about how the society treated women in Old France, encouraged me to explore old French law and, by extension, Quebec law. A quirk of local history means that Old French law remained one of the living sources of the modern law of the family in Quebec until the 1990s. The result is that Quebec jurists have had a longstanding interest in the law of old France for their everyday work and, as a result, have always been comfortable with the idea that the 16th century Coutume de Paris can be studied to understand the law in force. Old French law books are treated not just as historical artefacts in Quebec, but as legal texts that could be studied to learn the law until recently where they were overtaken by modern family law reforms.

This unique legal history, together with the generosity of a Montreal lawyer with a scholarly eye, explains how some of France’s rarest old law books found their way into a library in Montreal. This collection of old French private law is indeed a treasure worth seeking out. What better way to do so than during my year abroad and in preparation for the dissertation due in my final year? I assure the reader: the purpose of this article is not to advertise the (wonderful) Modern Languages course I am taking at Oxford nor is my design to recruit students to study law in Canada. It is rather to share the gem that is the Wainwright Collection with linguists and historians of France who may not have the chance (or the inclination) to travel across the pond to icy-cold Quebec.

The story of how these old, sometimes soiled, tattered and faded books —surviving ‘the ravages of time and man, the terrors of the French Revolution, the destruction of two world wars, and safely made its modern odyssey by sea from Paris to Montreal’[2]— made their way from Paris, France to Montreal, Quebec is a fascinating one.

Some historical context helped me understand the curious story of the Wainwright Collection. When France colonised North America as of 1534, its religion, customs and laws were enforced on the Indigenous people and French expatriates of what they called Nouvelle-France (New France) at the time. In 1626, the Coutume de Paris – the basic private law that applied to the region in and around Paris – and thus the civil law tradition was implemented for habitants of what is today’s Quebec. The “Civil Law” became the only legal system that Nouvelle-France followed for private law, although English criminal law was imposed soon after the “conquest” of Quebec in the 1760s. What later became Quebec has kept the French civil law and English common law for most public law to this day despite Canada becoming an independent country in 1867. Oddly, the Coutume de Paris survived in Quebec, in the form of the “Civil Code of Lower Canada”, even though France ceased to live by old French law when it adopted the Napoleonic code in 1804. Quebec’s bi-juridical system, with its connections to old France and to English common law, has been of interest to many legal and historical scholars.

François Olivier-Martin (1879–1952), the leading French legal historian of his generation, had an abiding interest in ‘la vieille France’ (Old France) and was an admirer of civil law and the Coutume de Paris. Olivier-Martin gathered together the works for this collection over his long career as a scholar – primary sources of published customs applicable in different regions of France, secondary materials, including doctoral theses published, and unpublished, by his students of over fifty years. This was his private research library of historical sources of French private law while he taught law in Paris that had no analogue in public collections. As a scholar, Olivier-Martin is best known for reconstructing and articulating a history of the Coutume de Paris which is reflected in the 1200 works in his library. To this day, contemporary scholars use the collection for research not only on the law of old France, but also on Olivier-Martin himself.

The works are regarded as a reflection of the life, personality, or character of its former owner and collector. According to Dean of Law at McGill at the time the gift of these books was received in the 1950s, W. C. J Meredith, Me Olivier-Martin had himself expressed his desire that a Quebec university acquire his collection given the connections between Quebec and old French law. At Olivier-Martin’s death, Arnold Wainwright, a prosperous Montreal lawyer and graduate of McGill, bought the collection for the University from the French professor’s widow, hoping that it ‘would encourage graduate and undergraduate research into the Quebec Civil Code’.[3] The books were packed into six crates, sent from Paris to Le Havre, and then shipped to Canada on board the "S. S. Montreal."

In addition to practising law, Arnold Wainwright (1879-1967) was something of an amateur scholar and bibliophile: he taught Civil law part-time at McGill University from 1909 to 1934 and amassed a large library of old civil law books himself, which was added to the “Wainwright Collection” at his own death. He also bequeathed the residue of his estate to the University, which currently sustains the Wainwright Lectures, the Wainwright Fellowships, the Wainwright Legal Essay Competition, the Wainwright Scholarships for law students and of course, the historical Wainwright Collection in the Library. Importantly, legal historians join students from the world over – from Oxford and even from France – to the relatively small and dusty Wainwright Reading Room to undertake research on old France in Montreal, part of the former “New France”!

As I am enchanted by this tiny, beautiful library and overwhelmed by its own fascinating history – so much so I have been having some genuine trouble choosing the right topic from all the options for my dissertation. I may be simply experiencing ‘year abroad procrastination’ by exploring the history of the Wainwright collection as much as navigating its contents and for instance, writing this article, although I prefer to think that this is all part of a broader research process that I am undertaking. And I have been putting things off by reading the books for the Goncourt competition in that secluded library rather than the Coutumes of Paris – but it seems to me that this is a year where the “scolaire” may take a backseat to the “parascolaire”!

[1] As recounted by the dean of law at McGill at the time: (2007) 52 McGill Law Journal 209.

[2] M. L. Renshawe and J. E. C. Brierley, ‘Sources of Civil Law : The Wainwright Collection’, Fontanus 1988 Vol. 1, p. 77

[3] Montreal Star, Monday, February 10, 1958, 8.