Congratulations on your book. We all know about the Biblical Salome. Can you tell us more about the paradigm of the “Anti-Salomé”?

L’Anti-Salomé aims to shed a new light on the fin de siècle and the Victorian era through questioning the alleged opposition between deadly female characters and sacrificial female characters. It is hard to define “decadence” as matters of style, themes and axiology are intricately mixed. Many valuable critics (Mario Praz, Mireille Dottin-Orsini, Lisa Downing) have focused on the creation of the “femme fatale” in that period. By causing the death of Saint John the Baptist, Salomé epitomizes a deadly femininity that undermines the advent of a sound prophetic and poetic speech. L’Anti-Salomé aims to look at figures of benevolent femininity that do not fall under this “deadly woman” spectrum. The Virgin Mary, Eve, Lilith, Joan of Arc, Mary Magdalen, as well as androgynous female Orphic characters, can be read as representations of benevolent femininity that challenge the usual associations between seduction and evil. To a certain extent, they can all be fatal insofar as they help the fulfilment of the fatum. Another angle to L’Anti-Salomé is to read it within the wider frame of current cultural studies and gender studies. It has often been argued that the sacrificial femininity presented in Victorian and fin-de-siècle literature is a harmful model. I wish to put the notion back in a historical context where sacrifice was, chiefly, a male duty, and where benevolence was considered a sign of strength, not of weakness. More importantly I wished to focus more on the way some novels are built around sacrifice as a touchstone for benevolence. Modern sensitivity looks reluctantly at sacrifice and selflessness, but they were all the rage after the collapse of the Second Empire. Once all the heroes are dead, it is the female character who endorses an Orphic or Christ-like legitimacy to deliver a word of salvation—that is to say, a word that would help move out from Decadence.

Who are the main authors you study in your book?

As the book intends to bridge gaps between minor and major late-19th-century writers, I selected authors who are representative of the variety and nuances of thought in the post-Baudelairean era. The book stemmed from my readings of Baudelaire and Wilde, and draws parallels between Zola, Newman and Renée Vivien, Marcel Schwob and Marie Corelli, Léon Bloy and George Macdonald, and also looks at works from forgotten writers who were famous and influential in their day: Jeanne de Tallenay, Jean Lorrain, Catulle Mendès and Jean Bertheroy. The main references I use are Hélène Cixous, René Girard, Vladimir Jankélévitch, and Julia Kristeva; I also tried to draw from what the writers I look at knew of Christian and Pagan traditions, hence the presence of Ovid and Tertullian.

Is there a particular text of the period which you would recommend to modern readers?

I fell into fin-de-siècle literature when I read Jean Lorrain’s Monsieur de Phocas. It is often presented as a pastiche of À rebours and a typical example of fin-de-siècle style, both in terms of writing and of storytelling. An easier read might be his Princesses d’ivoire et d’ivresse. Lorrain is clearly underrated.

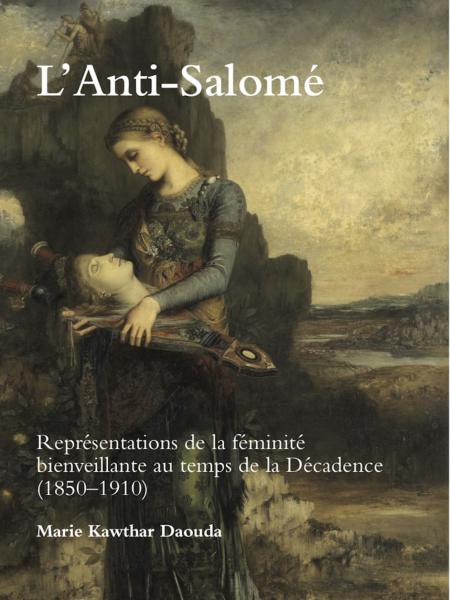

Illustration plays a large part in the book. Tell us about your choice of cover.

The cover I chose is Orphée by Gustave Moreau. French fin-de-siècle was obsessed with Moreau’s paintings. Huysmans met him through Jean Lorrain and was so smitten that he wrote fascinating pages about Salomé and L’Apparition in À rebours. Orphée presents a similar face-to-face between a male and a female figure to the one in L’Apparition. In his ekphrasis of the latter, Huysmans gave voice to the two characters. In Orphée, however, their silence is open to interpretation. The female figure could be responsible for the poet’s death; but she could also be the one now chanting words of consolation. The first time I saw this painting was when I was fifteen, right after I was introduced to Lorrain, my French teacher used it for teaching artistic commentary. A few days later, I found a copy of Les Fleurs du mal with it as a cover and devotedly kept it. Moreau’s Orphée has somehow always remained as a filigree in my studies and research.

What got you interested in French literature in the first place?

« Je suis tombée dans la marmite quand j’étais petite! » 1

How are you enjoying Oxford?

I like it more every day. When lockdown happened, I did not even try to go elsewhere, as I enjoyed my deserted college and the eerie silence of the empty streets. In the misty dusk, one would think of Baudelaire’s translation of Quincey’s “Visions d’Oxford”. Lockdown made me realise Oxford is my home now. Each stone, each spire tells a story. I love the idea of walking where Wilde, Hopkins and Newman used to walk, and imagining characters from Zuleika Dobson or from Brideshead Revisited strolling around. To be honest, I love “normal” Oxford too and was quite thrilled to see people coming out again. The balance of teaching and research, of thrilling conversations, of quiet studying and solitary ambling, is all I could wish for. I am very much looking forward to meeting my students again.

What are you working on now?

I am now looking at another side of the nineteenth century and how it grows into the entre-deux-guerres though a project which studies “desperate prayer” from Baudelaire to Bernanos. Baudelaire’s poems provided the two next generations (Huysmans and Bloy then Mauriac and Bernanos) with a form of expression that owes a lot to the despair expressed by the prophets in the Bible, and this despair takes the place of the enthusiastic speech displayed by Hugo. The purpose of the analysis is to show that the despair faced by the post-1848, post-1870 and post-1914 generations led to the collapse of trust in language as a means to change the future by moving people’s hearts, but that this powerlessness of human speech actually gives way to a higher form of poetical discourse, an attitude of expectant hope within despair—"hope against all hope” —that takes shape in the narrative form rather than in the poem.