In early 2016 plans to relocate the Slavonic Library from its offshore haven in Wellington Square to the Taylorian were well under way and the process of matching up space requirements had been largely a matter of measuring the length of shelves. To my surprise I was contacted in January of that year by Amanda Saville, then Librarian of The Queen’s College, who wondered whether I had a view as the college lecturer in Russian on what should be done to the Morfill Collection. So far as I knew at the time, the name referred to a modest set of books housed in a special store at 47 Wellington Square that had once attracted my interest because of its copy of a second edition of Nikolai Karamzin’s great history of the Russian state. As it turned out the entire collection belonged to Queen’s and had been on loan to the Taylor Slavonic Library from 1936. With its move to a small location, TABS was being culled, and while Queen’s was by then building its own splendid new library building, including a state-of-the-art book and manuscript repository, Morfill was on nobody’s radar. Wither Morfill? The question of storage became one of ownership. Did the College wish to rehouse the books on its own site or relinquish ownership to the Bodleian Libraries? Amanda Saville’s question, therefore, was whether the collection had any value and whether it was of interest. My first reaction was to ask to see the catalogue as the logical starting point only to discover that the collection had apparently never been inventoried. There was no record of titles much less notional sums. I suggested to Queen’s that they commission a professional to provide both a bibliographic record and a valuation.

Enter Joanna Skeels. Joanna had read Russian at St Edmund Hall and after going down had taken a job at the very distinguished antiquarian bookseller Bernard Quaritch, where her portfolio included Russian books. Over the years I’d seen her work in the superbly researched catalogues that emanated from the firm. The meticulous scholarship wasn’t entirely a surprise since I’d come to appreciate Joanna’s devotion to her subject when I was her undergraduate tutor and over the years she’d sent some fascinating materials she thought might be of interesting (including some Pushkiniana of great research interest). Joanna accepted the commission from Queen’s and with her characteristic brisk efficiency got on with the job. I heard nothing from her until May 2016 when Amanda sent me the catalogue, which proved to be a delight and revelation.

William Morfill (1834-1909) has not remained a household name but his pioneering contributions to the establishment of Russian and the Slavonic languages in Oxford were commemorated with a blue plaque at 42 Park Town, where Morfill lived from 1863 to 1899. His evangelism for his cause— Russian was not one of the original languages represented in the Taylorian Library—was the subject of his inaugural lecture as the first Professor of Russian in 1900 only four years before Russian became a full degree subject at Oxford in 1904. Evidence of his distinction can also be found in the extensive tribute paid to Morfill in an obituary by Russian Academician, Ia. K. Grot, one of the great archival scholars of Russian literature, that praised him ‘as a friend of Russia’ while also describing the ‘considerable chagrin and grief that the deep ignorance of his compatriots caused him’ in his efforts to establish Russian as a university subject. The evidence of his learning and wide spectrum of interests is visible in his publications, which range from grammars of Polish, Russian, Bulgarian and Czech to works of popular history such as The Story of Russia (1890) and A History of Russia from the Birth of Peter the Great to the Death of Alexander II (1902). As Dr Gerald Stone FBA noted in his DNB article, ‘his knowledge extended to less well known Slavonic languages such as Polabian and Sorbian, and beyond the Slav area, for instance to Georgia, which he visited in 1888.’ Morfill travelled widely in the Slavonic lands, visiting friends, libraries, and buying pamphlets and books. The title page of his book Slavonic Literature (1883), published in the series ‘The Dawn of European Literature’ by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, begins with a quote from Pushkin asking ‘Shall the Slavonic streams flow into the Russian sea? Or that be dried up? That is the question.’ Morfill’s answer was clearly not if he could help it. His most lasting contribution might therefore be the donation he made to The Queen’s College, Oxford of which we now have a much clearer picture.

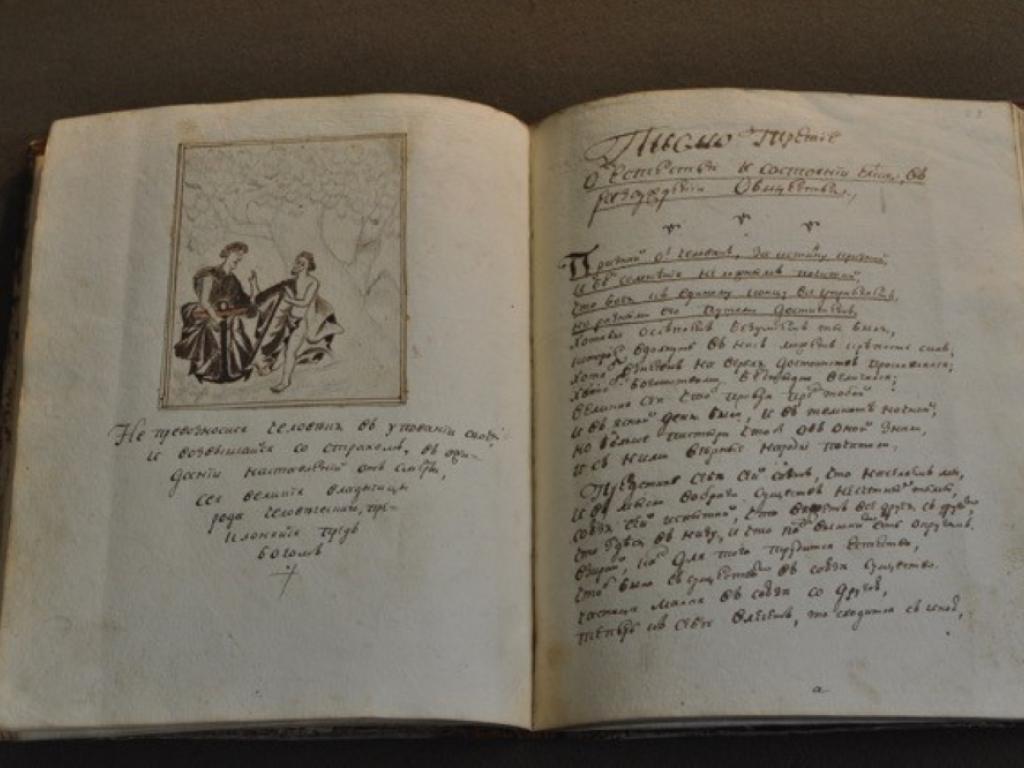

There are over 4000 volumes. General histories, language manuals, translations, and works of travel literature (including some little known seventeenth-century works on Ruthenia) form a large part of the collection; they probably constitute Morfill’s working library. Of greatest value are about sixty items that reflect Morfill’s connoisseurship as a bibliophile. Among the highlights are a practical grammar of English written by Mikhail Permskii and published in 1766, of which this is the only known copy worldwide (the British Library only has a photocopy); eighteenth-century rarities include early editions of canonical authors such as the polymath Mikhailo Lomonosov and the Russian Boileau, Alexander Sumarokov, as well as translations into Russian of Bunyan, Fielding, Smollet, and Edward Young’s influential Night Thoughts. Of particular note is a very rare manuscript copy of a translation of Alexander Pope’s Essay on Man acquired by Morfill in 1884. The original translation, a celebrated work by Lomonosov’s pupil Nikolai Popovsky, was made from the French prose version of Étienne de Silhouette. It was subjected to Church censorship and reissued with cuts. This manuscript book is one of a small number of clandestine copies made from an edition printed by Moscow University Press in 1754 and it contains lines restored from the original edition. It also contains five manuscript illustrations, four of which copy the engravings included in the original printed book, a point of note for book historians since eighteenth-century Russian books rarely contained engravings (see illustration). It was a pleasure to consult the manuscript when I was working on Part III of the History of Russian Literature (Oxford, 2018). Other gems include a clutch of rare first-editions of Alexander Pushkin. These sit alongside nineteenth-century sets of classics such as Gogol, Goncharov, and Tolstoy. Morfill also had an eye for the literature of his own time and collected fin-de-siècle Russian poetry, amassing a splendid collection of poetic books by Konstantin Balmont, some of which bear presentation inscriptions, and a 1904 translation of Oscar Wilde’s Salome and the Ballad of Reading Gaol. True to his double patrimonies as an Englishman and a Slavist, Morfill also amassed approximately 55 translations of Shakespeare’s plays in Czech and Slovak. The Morfill collection now forms one of the highlights of the East European Special Collections, along with the Dawkins collection, as resource and adornment a near equal to the treasures in the Voltaire Room.