Who expected Camus’ 1947 novel, La Peste, to come to life as it has done this year? The narrative revolves around the outbreak of plague in Oran and subsequent quarantine with the reactions of the townsfolk. When reaching for this title, are we, on some level, looking for ourselves in these characters? A surge in sales of the novel perhaps reflects the fascination reactions to crises inspire, and our need to decipher our own responses.

Camus described his plague as “sans avenir” [having no future]. He was writing when the world was still reeling from two World Wars. His native country, Algeria, was experiencing mounting violence that would culminate in independence from France in 1962. Famously avoidant of overt political statement, Camus observed in his acceptance speech for the 1957 Nobel Prize that the agenda of his generation was not to reform the world, but to “empêcher que le monde se défasse” [prevent it from destroying itself]. His letters indicate that he did not write his depiction of an epidemic as an allegory for any entity or event but rather to serve as a mental exercise in “what if…?” It therefore seems fitting to consider some comparisons with our experiences. Can we relate to the reactions to disease, quarantine, and isolation which Camus described?

We must not forget those for whom illness was already a hardship

The short introduction to La Peste portrays the normality of everyday life before the plague, in contrast to the chaos the epidemic wreaks. A striking paragraph describes how inhospitable the city is, should one become unwell.

Un malade a besoin de douceur, il aime à s’appuyer sur quelque chose, c’est bien naturel. Mais à Oran, les excès du climat, l’importance des affaires qu’on y traite, l’insignifiance du décor, la rapidité du crépuscule et la qualité des plaisirs, tout demande la bonne santé. Un malade s’y trouve bien seul.[1]

This strikes a chord with the experiences of many disabled people. As disability advocates everywhere have reminded us: whilst lockdown will eventually end for most, we must not leave behind those for whom restriction and isolation were already the harsh reality of everyday life and will continue long after the pandemic ends. In an Instagram Live video, actress Miranda Hart said, "chronic illness is lockdown…imagine being the only one in lockdown. Imagine everyone else doing all that you desire and you being stuck at home". The UK disability charity Leonard Cheshire expressed their hope that “if any positives can come from [the charity’s awareness campaign] coinciding with lockdown, non-disabled people have a deeper understanding of the invisible struggle disabled people face every day.”

Routine is our coping mechanism

The introduction to La Peste emphasises the order and structure of life in Oran. Quarantine is distressing, not so much in that it denies people freedom but because it disrupts the routine that otherwise sustains them. This becomes acutely apparent in the second part of the novel, once quarantine is enforced:

Personne n’avait encore accepté réellement la maladie. La plupart étaient surtout sensibles à ce qui dérangeait leurs habitudes ou atteignait leurs intérêts.[2]

Is this a part of how we react to changes we cannot control? Camus reflects on self-indulgent aspects of human nature in the diverse emotional responses of Oran’s townsfolk, creatures of whim and habit – not driven by freedom, but by comfort.

Routine is the crutch upon which we lean under duress. The main character in La Peste, Doctor Rieux, carries a heavy responsibility throughout the epidemic. Once infection rates start to soar, all he can do is carry out his job to the best of his ability: “L’essentiel était de bien faire son metier.”[3] With such uncertainty and upheaval, the bigger picture can feel impossible to ascertain. Instead of trying to rationalise everything at once, focusing on a single priority feels more manageable.

Impossible communications during quarantine

Whilst the extraordinary situation provides a common experience, once the novelty wears off, what is there to talk about?

In La Peste, people struggle to find news, thoughts or queries to impart in telegrams to the outside world (letters are banned in case they transmit the infection). They resort to banal phrases; there is little else to say.

…de longues vies communes ou des passions douloureuses se résumèrent rapidement dans un échange périodique de formules toutes faites comme : « Vais bien. Pense à toi. Tendresse. »[4]

Our heightened connectedness provides greater remote communication than ever before. But whilst we may be messaging loved ones for a catch-up, how easy is it to make interesting conversation when our plans have been changed and we haven’t left the house? How many of us have experienced that moment of doubt when asked “So, what have you been up to?” Er…

Camus hints at how highly people value connection, even if it is empty. Little though we care about that Zoom quiz, we just want to see the faces of the people we love.

Reconsidering relationships

Camus portrays lovers as the most “interesting group” for the level of introspection the epidemic provokes:

Ils se trouvaient tourmentés par d’autres angoisses au nombre desquelles il faut signaler le remords. Cette situation, en effet, leur permettait de considérer leur sentiment avec une sorte de fiévreuse objectivité. Et il était rare que, dans ces occasions, leurs propres défaillances ne leur apparussent pas clairement.[5]

Being kept apart or stranded together can put pressure on any relationship. Camus implies that enforced separation can provide space to evaluate the relationship with added perspective.

Camus’ portrayal is a romantic one. In our reality, whilst in many cases the strain on relationships may have been remediable, for others, the consequences of stress, uncertainty and isolation have been grave. The UK’s largest domestic abuse charity, Refuge, reported a 700% increase in calls to its helpline in a single day during lockdown.

Escaping outdoors

Did you notice more people out walking over lockdown? Did you or people around you venture further afield in search of new routes? As venues close, the townsfolk of Oran flock to the streets to escape the four walls of their homes.

Le nombre des piétons devint plus considérable et même, aux heures creuses, beaucoup de gens réduits à l’inaction par la fermeture des magasins ou de certains bureaux emplissaient les rues et les cafés.[6]

Spain’s lockdown forbade people from leaving home except to take out waste or walk a dog, leading to a marked increase in people trying to adopt dogs as an excuse to go outside. Animal rescue organisations and public prosecutors issued warnings about the increased risk of these animals being abandoned after restrictions were lifted.

Statistics become ambiguous

Camus writes of the unnerving ambiguity of statistics in the early stages of quarantine: as people do not know what a normal death rate is, they do not know how seriously to take figures surrounding the plague – and, by extension, the plague itself.

En effet, l’annonce que la troisième semaine de peste avait compté trois cent deux morts ne parlait pas à l’imagination. D’une part, tous peut-être n’étaient pas morts de la peste. Et, d’autre part, personne en ville ne savait combien, en temps ordinaire, il mourait de gens par semaine. […] Le public manquait, en quelque sorte, de points de comparaison. Ce n’est qu’à la longue, en constatant l’augmentation des décès, que l’opinion prit conscience de la vérité. La cinquième semaine donna en effet trois cent vingt et un morts et la sixième, trois cent quarante-cinq. Les augmentations, du moins, étaient éloquentes.[7]

Camus’ portrayal of the citizens’ struggle to interpret the mortality statistics extends to characterise the collective distrust of numbers, reporting and authority.

Whilst attitudes have varied widely, our understanding of the statistical impact of the pandemic has had to evolve: in August, Public Health England changed the definition of “COVID-related deaths”. This changed the toll of those who lost their lives to the virus.

A focus on frontline Health Workers

As the epidemic takes hold and hospitals become overwhelmed, the citizens of Oran start to organise themselves into teams to meet the needs of those requiring care which cannot otherwise be provided. This includes making arrangements for the recently deceased.

Ces formations aidèrent nos concitoyens à entrer plus avant dans la peste et les persuadèrent en partie que, puisque la maladie était là, il fallait faire ce qu’il fallait pour lutter contre elle. Parce que la peste devenait ainsi le devoir de quelques-uns, elle apparut réellement pour ce qu’elle était, c’est-à-dire l’affaire de tous.[8]

Camus appears almost to trivialise the decision of Oran’s citizens to volunteer. However, the apparent calmness of the narrative voice describing the otherwise brave and purposeful actions is due to the motivation behind them. The character who coordinates this response, Tarrou, describes this motivation as “understanding”. Based on compassion, acceptance, a sense of responsibility, or all three, an echo of this collective response can be observed in 2020. In March, the NHS Volunteer Responders recruitment initiative recruited 750,000 people, just two days after the target was increased, having hit its initial 250,000 target in under 24 hours.

What can we take from this?

Camus’ is an exploration of spiritual and philosophical questions which arise in times of disruption, but in no way seeks to promote a single “right” way to respond. Whilst Camus strove to separate himself from the label of Existentialism throughout his lifetime, his most famous works impart a message of living freely, passionately and responsibly in the face of the Absurd (a meaningless existence), of constructing one’s own purpose in a world without meaning.

This is then, perhaps, Camus’ most comforting message about his depiction of an epidemic: it has no moral meaning.

Moralité de la peste : elle n'a servi à rien ni à personne. Il n'y a que ceux que la mort a touchés en eux ou dans leurs proches qui sont instruits. Mais la vérité qu'ils ont ainsi conquise ne concerne qu'eux-mêmes. Elle est sans avenir. (Camus, Carnets)[9]

Camus’ plague did not “stand for” anything; it has no intrinsic value. The novel’s focus is on how the community of Oran responds to a crisis. The portrayal is not one of judgement, but of compassion. How characters react to the plague is not a matter of whether they were right or wrong, but rather a matter of each individual’s ongoing struggle under different personal ordeals. Camus’ philosophy of finding our own meaning in a meaningless predicament may feel more pertinent now than in living memory – but he argues that we should not lose hope in the face of the Absurd.

Living passionately and responsibly is Camus’ message. If he were writing our story, he would write it with compassion.

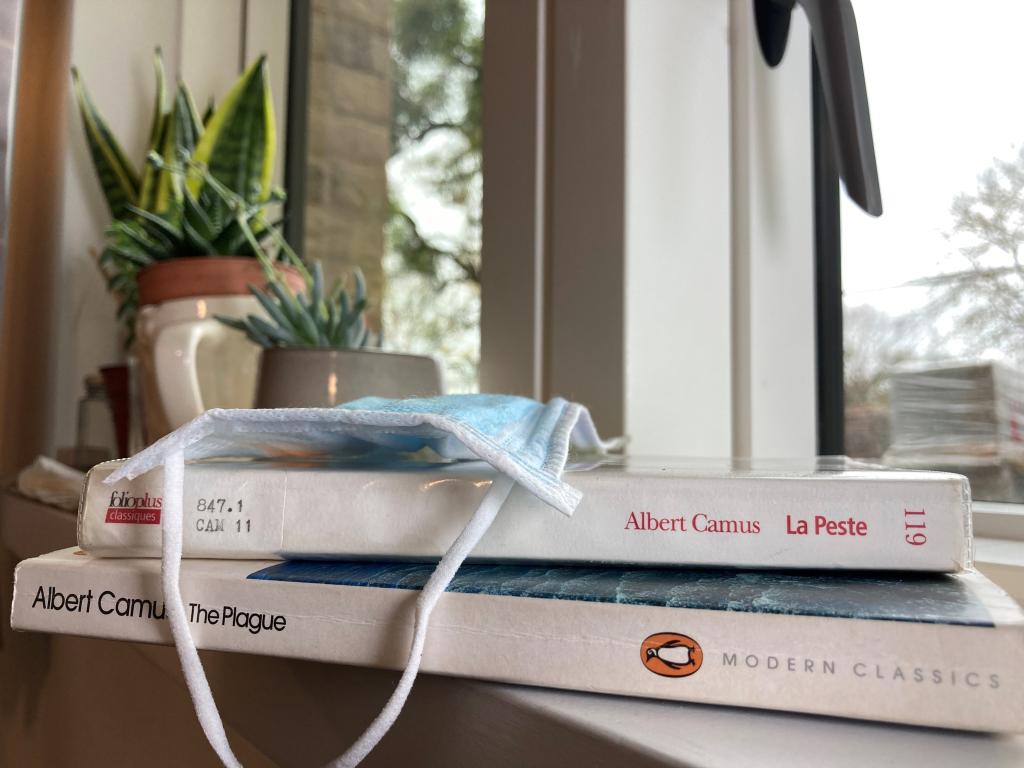

Catherine read La Peste in the 2008 Folioplus Classique edition. The translations in the footnotes are by R. Buss in The Plague, Penguin Classics, 2013.

[1] [A sick person needs tenderness, he quite naturally likes to lean on something. But in Oran, the extreme climate, the amount of business going on, the insignificance of the surroundings, the speed with which night falls and the quality of the pleasure, all demand good health. A sick person is very lonely here.]

[2] [No one yet had really accepted the idea of the disease. Most were chiefly affected by whatever upset their habits or touched on their interests.]

[3] [The main thing was to do your job well.]

[4] [… Long lives together or painful passions were reduced to a periodic exchange of stock phrases such as: 'Am well’, ‘Thinking of you’, ‘Affectionately yours’.]

[5] [They were tormented by other anxieties, one of which was remorse. This situation, in fact, enabled them to consider their feelings with a sort of feverish objectivity. And it was rare that, on these occasions, their own shortcomings were not made clear to them.]

[6] [The number of pedestrians rose and, at slack times, many people, who had been reduced to inactivity by the closing of shops and some offices, filled the streets and cafés.]

[7] [The announcement that there had been 302 deaths in the third week of the plague did not stir the imagination. On the one hand, perhaps not all of them died of plague. And, on the other hand, no one in the town knew how many people died every week in ordinary times. […] So in a sense the public had no point of comparison. It was only in the longer term, by noting the increase in the death rate, that people became aware of the truth. The fifth week produced 321 deaths and the sixth 345. These increases, at least, were convincing.]

[8] [The teams helped the townspeople to get further into the plague and to some extent convinced them that, since the disease was here, they had to do whatever was needed to be done to overcome it. So, because the plague became the responsibility of some of us, it appeared to be what it really was – a matter that concerned everybody.]

[9] [The moral message of the plague: it was of no use to anybody. It is only those whom death has touched, or their relatives, who have learned anything. But the truth which they have thus conquered concerns only themselves. It has no future.]