Dante’s most famous work, the Commedia, records the journey of the Dante-pilgrim through the three realms of the afterlife, Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, which correspond to the poem’s three cantica. The Commedia has had an enormous influence on Western culture in the seven centuries following its creation and continues to be enjoyed, discussed, and debated by readers today.

My work focuses on a small section of the second cantica, Purgatorio, called the Ante-Purgatory. Dante-pilgrim and his guide, Virgil, emerge from Hell into Purgatory which is imagined as a huge mountain. This mountain is divided into seven terraces where souls must do penance according to the vice (or more likely, vices) which they suffered from on earth: pride, envy, wrath, sloth, avarice, gluttony, and lust. This penance takes the form of a physical punishment (poena sensus) which induces correction of the vice. For example, on the first terrace, the prideful are doubled over under heavy rocks and are constrained by the heavy load to look down at examples of humility engraved on the floor. The envious appear on the second terrace with their eyes gruesomely sewn shut as they derived pleasure from seeing others fail or brought low.

Ante-Purgatory (or antipurgatorio) refers to the landscape through which the Dante-pilgrim and his guide travel in the first nine cantos. It is a liminal, perplexing and greatly understudied element within the Commedia where souls wait to begin their penance in Purgatory-proper, beyond the gates of Purgatory on the terraces. Ante-Purgatory has no precedent in theological works of Dante’s time or in contemporary folklore and is never named or explained by Dante; the name is instead the invention of commentators. This obviously leads one to ask why Dante would invent an area within Purgatory where apparently no penance take place, where souls can only wait to begin penance and, therefore, their progress up the mountain towards Paradise.

Though my work on Ante-Purgatory began long before 2020 hit, studying this liminal zone has become particularly pertinent to our current situation. Many of us have had to come to terms with, or are continuing to struggle with, the difficulties of waiting. I am reminded of an anecdote, apparently famous among architects, in which management staff in a skyscraper in New York received a number of complaints about the speed of the lifts. Employees were annoyed about how long they were having to wait for the lift, so the company brought in engineers in attempt to reduce wait times but were told it wasn’t possible. However, a psychologist in the building came up with a different solution. He installed mirrors outside the lifts. Now, while waiting for the lift, the employees could check their appearance and look at themselves and others while waiting, thus eliminating the boredom attached to the wait and thereby the frustration. The complaints stopped and many employees applauded the management for having increased the speed of the lifts.[1]

In Dante’s Ante-Purgatory, souls have to wait much longer than a minute or two for a lift. The excommunicated, for example, must wait three times the amount of time they spent outside the Church before death, while the negligent must spend the equivalent of their lifetime on the mountain’s slopes. Dante’s Ante-Purgatory provides an interesting opportunity to think about modes of waiting in a particularly extreme setting and to reflect on how we deal with it.

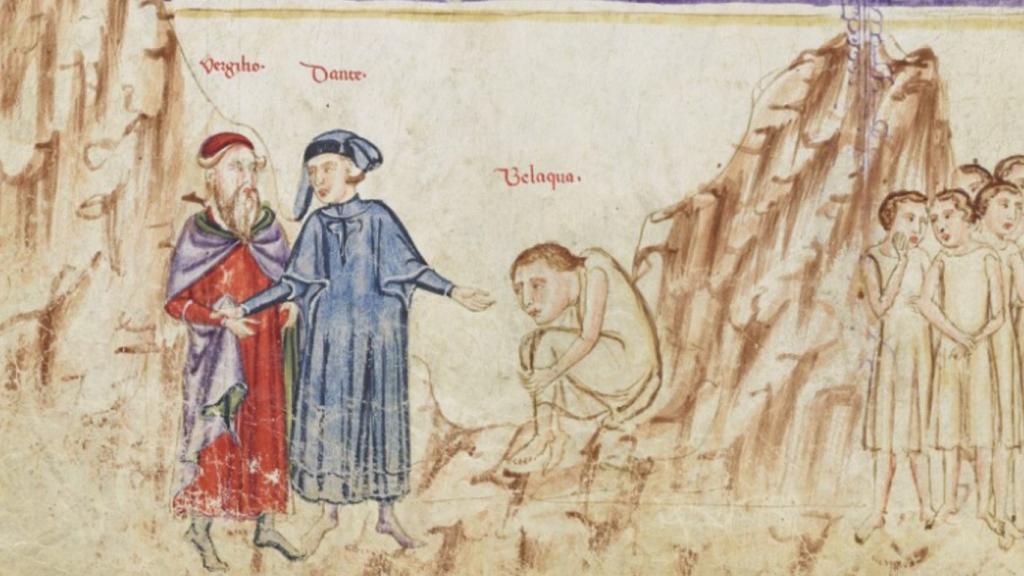

The Dante-character encounters some souls who appear to despair at their predicament and who languish under the weight of knowing that they must wait a lifetime to begin their climb. Belacqua hauntingly asks in Purgatorio IV: “O frate, andar in sù che porta?” / “O brother, what good would climbing do?” (127). Belacqua finds himself in Ante-Purgatory for his negligence, and his period of waiting does not appear to have cured him of his lazy tendencies, as Dante describes him as: “più negligente / che se pigrizia fosse sua serocchia” / “more negligent than if Sloth were his sister” (Purg. IV, 110-111). In Belacqua’s case, waiting a lifetime to ascend the mountain does not appear to have had any positive or corrective effect on his tendency towards negligence.

While Belacqua appears as the picture of laziness and despair, other souls in Ante-Purgatory appear to have more purpose. Virgil and the pilgrim are brought to the Valley of the Princes by the courtly Provençal poet Sordello who points out the souls of negligent rulers gathered there. As evening falls, the pilgrim notices that the rulers appear to be waiting for something to happen, and look towards the sky, “quasi aspettando”/ “as if almost waiting” (Purg. VIII, 24-26). Soon after, two angels appear and descend to take up defensive positions in the valley. Then, a serpent, representing the devil and recalling Genesis, slithers through the grass. The angels swoop down swiftly and drive off the serpent before returning to their defensive positions above. The same scene, which we understand is played out every evening, thus perhaps has a pedagogical function, directing the souls, on the one hand, to reflect on the Fall, but on the other hand, to turn towards God for protection and ultimately, salvation.

In Dante’s Ante-Purgatory, we see the importance of direction and purpose for humankind. Belacqua, an isolated and dejected figure, is weighed down in the knowledge that he must wait a lifetime to begin his climb, while in the Valley of the Princes, souls wait for the repeated scene, played out every evening, giving some direction and rhythm to their temporary exile from the mountain. In this unprecedented time, Dante’s Ante-Purgatory thus perhaps offers us a prism through which to think about modes of waiting, in full recognition of the fact that it can offer us an opportunity for focus and reflection, but equally can leave us, like Belacqua, disorientated and frustrated. Our experience of waiting perhaps depends, in part, on whether we can find some use in it.

[1] This anecdote is retold in an interesting article here: Jason Farman, ‘How to Wait Well’, Psyche, https://psyche.co/guides/how-to-think-of-waiting-as-a-chance-to-reinvent-the-future [accessed, 24th Nov. 2020].