Muscovy emerged during the period of Mongol suzerainty out of the north-eastern principality of Vladimir-Suzdal. Although Moscow was first mentioned in an early Rus chronicle in 1147, it was only in the 14th and 15th centuries that Moscow rose as the central place of an increasingly centralized state, loosely based around a vertical line of princes of the so-called Ruirikid dynasty of Rus. A fortified complex, the Kremlin, became the site of a church complex and the seat of princely power. With the reconstruction and expansion of the Kremlin under Ivan III (r. 1462-1505), public ceremonies developed, merging court ceremonial with Church ritual. Muscovite rulers participated in increasingly elaborate ceremonies and rituals that merged existing practices (such as enthronement) with a new set of sources of ceremony. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 saw the dispersal of Byzantine culture via churchmen and nobles, some of whom fled to centres of Eastern Christian networks in exile, such as Rome. A variety of networks brought sources from the Byzantine world, forming a new set of referents for a developing court culture. It was at the time of Ivan III’s marriage to the Byzantine princess, Zoë/Sofiia Palaiologina, who had resided in Rome following the seizure of the Despotate of Morea by the Ottomans, that the Kremlin gained part of its current landscape. Against this background of economic and territorial expansion and political consolidation, Ivan III sponsored an ensemble of palaces, churches, and fortifications that brought Moscow into the Renaissance.

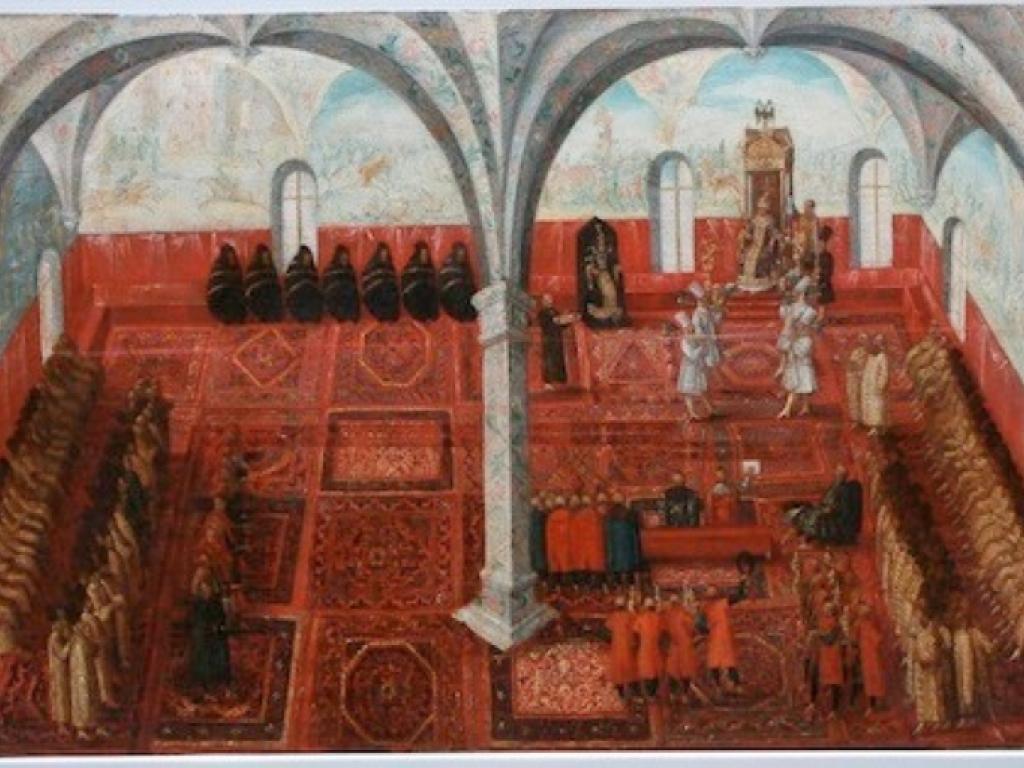

Part of Ivan III’s contribution to the complex was the Faceted Palace (Granovitaia Palata), embellished with depictions of biblical themes and the history of the Riurikid dynasty of early Rus. According to etchings of the room, this square chamber featured a thick rectangular pillar at its centre, which carried its high vaults under which the ruler presided seated up a throne located in the ‘red corner’ (krasnii ugol). The design of the room conveyed both political and spiritual legitimacy through its iconographic themes and constituted an arena for the performance of power. It is perhaps the procession to meet the ruler, described by the secretary to the Duke of Holstein, Adam Olearius, when he visited Moscow in 1633 and 1636, that best expresses the logic of the architectonic setting for the spectacle of power:

The audience hall was a vaulted stone square room, its floor and walls covered with lovely rugs, its ceilings decorated with Biblical paintings in colours off-set with gold. The throne (in the corner) was raised on three steps, surrounded by four silver pillars on which rested a canopy forming a little tower, at each corner of which was a silver eagle. His Tsarist majesty was seated on a throne attired in a robe set with precious stones and embroidered with large pearls. His crown, which he wore over a large sable hat, was encrusted with diamonds […].[1]

The Faceted Chamber was only one part of a great expansion project commissioned by Ivan III that commemorated the Grand Prince’s good fortunes, his victories over Kazan and Astrakhan, by creating a network of monuments (for example, the Sobornaia ploshchad/Cathedral Square, the Blagoveschensky sobor/Cathedral of the Annunciation, part of the Teremnoi dvorets/Terem Palace, etc.) that made visible both the continuity and ingenuity of Ivan III’s rule.

Within the strictly formal continuity of princely cultural patronage, ingenuity resides in the design and execution of the new princely residence and court structure by Italian architects such as Marco Ruffalo, Pietro Solario, and Aloisio da Carezano. Ivan III’s building programme and restructuring of court culture according to a new architectural logic reflect a transcultural set of influences where the internal logic to Ivan III’s rule finds its concrete expression through an Italian Renaissance architectural style, endowed with a new political legitimacy conferred by a Byzantine imperial connection. Zoë/Sofiia Palaiologina had resided in Rome and it may have been her connections (and those of her Romano-Morean entourage) that brought these architects to Muscovy. Very little is known about the Italian architects who came to Muscovy. One, Aristotele Fioravanti, from Bologna, had previously worked for the Medici family and is known to have designed the Palazzo Bentivoglio in Bologna. The palace bears some resemblance to the Faceted Palace. Another architect, Pietro Antonio Solari, completed part of the Duomo in Milan before arriving in Muscovy where he designed part of the Kremlin’s fortifications.

Received ideas insist upon the “modernizing” or “Europeanizing” oeuvre of Peter I, with the implication being that what was new in Russia in the 18th century was already old elsewhere, thereby contributing to outdated notions of Russia’s “backwardness” vis-à-vis its contemporaries to the west. This is why Muscovy in the 14th to 17th centuries is often entirely overlooked, or presented as still belonging to the medieval world, in spite of its temporal and ideological separation from the medieval polities of Rus. Historians of Muscovy are in agreement about the innovations that began with Ivan III’s ascension to the throne. Although many of Ivan III’s innovations remain obscure, primarily due to a lack of preserved source material, the age of Ivan III reflects new avenues of contact, dissemination, dialogue, and transmission between Muscovy and the wider Renaissance world.

[1] The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors sent by Frederick Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy, and the King of Persia (London, 1962), p. 17.