This term sees the publication of two volumes of essays – both co-edited with colleagues from the Faculty of Music – which speak to our multilingual world, as well as to the ways in which language learning is as central to other academic disciplines as it is to Modern Languages. Both books stem from conferences held in 2015 and 2019 respectively, and the process of editing them and checking the proofs brings back happy memories not just of hearing the original papers, but also of serendipitous conversations over lunch and dinner, spontaneous interactions during the many coffee breaks, and sociable trips to the pub at the end of a productive day. In these days of virtual conferences and seminars, it is perhaps the memory of those moments in particular which gives rise to a sense of what we have lost and what we most hope to regain.

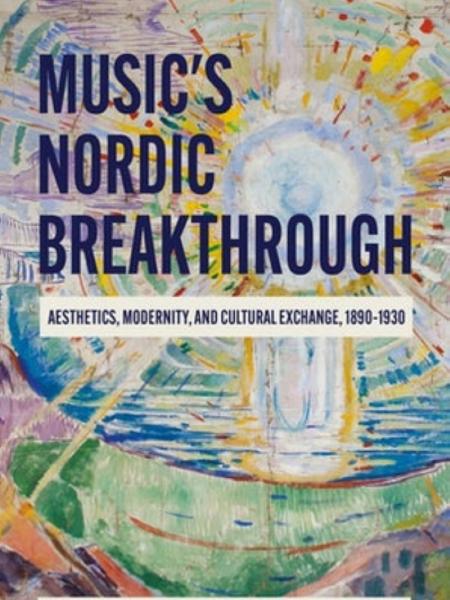

Music’s Nordic Breakthrough: Aesthetics, Modernity, and Cultural Exchange, 1890-1930 appears in February with Boydell & Brewer, and emerges from a conference I co-organised in 2015 with Daniel M. Grimley, Professor of Music and Douglas Algar Tutorial Fellow in Music at Merton College. Our original inspiration came from the realisation that 2015 marked the 150th anniversaries of three leading composers – the Danish Carl Nielsen, the Finnish Jean Sibelius, and the Russian Aleksandr Glazunov. Each composer was sure to be the subject of individual conferences in their respective homelands, but our thought was organise an event that sought to explore the interesting cross-border, transnational aspects of culture and the arts in the European North around the turn of the century. This regional approach is common enough when it comes to the Scandinavian lands – Denmark, Norway, Sweden – but we deliberately threw our geographical net a little wider, including the Baltic states, Russia, Great Britain, and Iceland. In doing so, we aimed to challenge accounts of European modernism focusing primarily on major capital cities such as Berlin, Vienna, and above all Paris. Instead, we wanted to turn our attention to the countries of the European North and examine their contribution to a broader Pan-European phenomenon. The geographical, cultural, and linguistic heterogeneity of the volume is matched by the variety of media it covers. We were delighted to be able to include contributions from art historians, theatre scholars, and cultural historians, learning much from their ideas about modernity, cultural exchange, and transnational approaches to the study of the arts.

It was also a particular pleasure for me to set my own interests in Russian culture in such a rich comparative context. Over the years, I’ve made many happy research trips to the National Library of Finland in Helsinki, as well as acquiring a very rudimentary reading knowledge of Finnish and Swedish in order to examine the interactions between Russian artists and their Finnish counterparts. This has helped me to rethink the way I look at nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Russia. Instead of looking at the world from the perspective of a vast imperial and colonial state, it becomes possible to give voice to the experience of the smaller nations that often find themselves caught up in complex geopolitical games. In similar vein, my chapter in Music’s Nordic Breakthrough is an examination of how Sibelius’s music helped early twentieth-century British musicians set aside an abiding preoccupation with empire and continental rivalries in favour of a productive dialogue with the emerging musical culture of a small country seemingly on the periphery of Europe.

Music’s Nordic Breakthrough treats the idea of translation in a distinctly expansive way, exploring the ways in which the arts help to convey culture across national, political, and linguistic borders. In Song Beyond the Nation: Translation, Transnationalism, Performance, the act of translation becomes more specifically verbal. Co-edited with Laura Tunbridge, Professor of Music and Henfrey Fellow and Tutor in Music at St Catherine’s College, Song Beyond the Nation is published in March by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Academy. The chapters in it were all initially presented at a conference held in Oxford in 2019, when we set the speakers the challenge of examining how the poetry of Hafiz, Heine, Verlaine, and Whitman had been set to music. There was a twist, however. Much writing on song – especially when it comes to the nineteenth century – is based on an assumption that there is a close, even organic relationship between language, nation, and music. We wanted to examine something rather different – namely, how song composers set foreign poetry, whether in the original or in translation, and how performers carry foreign repertoires across the borders of the nation. The geographical range turned out to be extraordinarily wide, with contributions covering Scotland, Boston, and Hawai‘i, as well as more familiar ports of call. But local nuances emerge too; French is seen from the vantage point of Belgium, and English is pulled between North America and Britain.

What links both volumes is the ubiquity of foreign languages in the world of the performing arts. Our Nordic conference included a recital given by Hedvig Paulig and Gustav Djupsjöbacka and featuring songs in Finnish, Russian, and Swedish by Kuula, Madetoja, Melartin, Merikanto, Rachmaninoff, and Sibelius. And my collaboration with Laura Tunbridge has roots in a series of longer-term relationships with organisations such as Oxford Lieder and Wigmore Hall, as well as in the work of the Oxford Song Network, co-convened with Alex Lloyd (German tutor at St Edmund Hall). From Scandi-noir TV series to the films of Almodovar, from surtitled Janáček operas to performances of Shakespeare’s dramas by visiting theatre companies, from Weimar cabaret to evenings of French chanson, foreign languages steal upon us and work their captivating magic, inviting us on journeys both real and imagined.