It was while working on my ‘bridging’ essay as a final-year undergraduate in Spanish and Arabic that I first came across Christina Civantos’ work on Latin American Arab literature—specifically, her rich and illuminating study of literary and cultural dialogues between Arab and non-Arab Argentine writers Between Argentines and Arabs (2006). That essay would later evolve into my DPhil project, which considers tradition as process—dynamic rather than unchanging—in twentieth-century Latin American Arab poetry.

‘Accept, to begin, that tradition is the creation of the future out of the past,’ writes Henry Glassie in The Journal of American Folklore (1995).[1] Too often levelled as a criticism against Global South and diasporic literatures, the word ‘tradition’ weighs rather heavy when taken in the static sense—of anachronism, hindrance, or trammel. In the case of Latin American Arab poetry, a number of scholars into the twenty-first century have faulted it for its purported tendency to tradition, which they attribute to the perceived lack of cultural development in both Latin America and the Arabic-speaking world. Meanwhile, they depict the United States as a bastion of freedom and progress, where writers from the Global South find themselves empowered to ‘break with tradition’: creativity can flourish, unstifled. Commenting on the Arabic-language poetry of Arab immigrants living in Spanish America, Civantos has noted how many scholars have ignored or dismissed it as ‘aesthetically insignificant in terms of Arab poetics’, especially when compared with its North American counterpart.[2] These ideas are rooted in a conflation of tradition with traditionalism, and in the association of tradition with the Global South and of modern sophistication with the Global North. But we find tradition everywhere: the new rests on the old; literary modernity on the texts that came before.

Tradition does not keep the ground from breaking, although our scholarly (and other) traditions here in the Global North could definitely do with some shaking up. As the Uruguayan critic Ángel Rama recognised, the ‘task of selecting traditions’ is a creative one;[3] and, against the paternalistic perception that vanguardism and the new originate in the West and are only belatedly imported elsewhere, he rejected portrayals of Latin American literary cultures and forms as crude distortions or importations of European models. We put Global South and racialised diasporic writers in a double bind when we set proximity to Western-ness as a measure of success, and all the while they still carry the burden of ‘ethnic’ representation: expected to assimilate, but judged to be copycats, inauthentically themselves, if they do so.

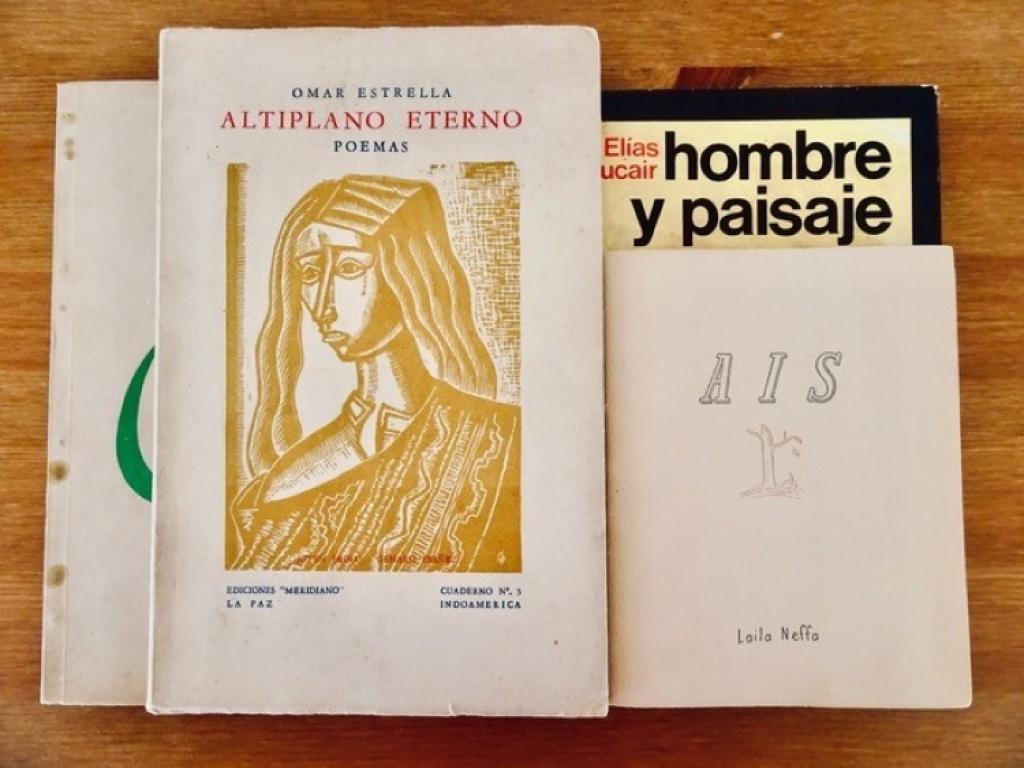

Where cultures converge, they are transformed by one another. In drawing from, and writing across, traditions, we can do something different with them; create something unique and original. The poets whose works I am studying are not mere imitators of style, nor do they ‘tend to tradition’ in the same way. Take, for instance, the Spanish-language poetry collection Ais (1951) by the Uruguayan-born Lebanese Argentine poet and translator Laila Neffa (b. 1925): a radical reworking of the Majnun Layla legend, the semi-historical story of Layla al-‘Amiriyya and Qays ibn al-Mulawwah, two seventh-century Arab Bedouin poets whose forbidden love resulted in madness and death. Excitingly, Neffa’s version of this classic tale of unfulfilled love involves a reversal of gender roles, Spanish sonnets, Arabo-Persian ghazals, and (or so I argue) a Borgesian mirror—traditional and novel at once. Another poet, Omar Estrella (d. 1991), who grew up in Bolivia but spent much of his life in exile in Argentina, was a practitioner of Marxist-Leninist indigenismo active in the Andean political and cultural avant-gardes. His poems are in conversation with the ideas of Latin American socialist thinkers such as José Carlos Mariátegui (Peru) and Tristán Marof (Bolivia), whose discourses of revolution incorporate (and not at all unproblematically) Indigenous peoples. Even as Estrella decries colonial violence and racial capitalism, he violently instrumentalises and aestheticises Indigenous communities, labour, and sexuality for his own vision of change. These authors are not passively subject to tradition, but themselves wield power over it.

We find tradition everywhere, but whose literary and artistic traditions are more frequently cast as hindrances to creativity and cultural development? Whose traditions are more likely to be hailed as revolutionary, modernising influences? Far from being derivative and lacklustre bodies of work, Latin American Arab and other south-south poetries call for language beyond ‘imitation’, ‘influence’, and ‘assimilation’—beyond vocabularies tied to Western and Western-centric notions of development and progress. Perhaps it is our ways of reading that are mired in tradition, rather than the poetry itself.

[1] Henry Glassie, ‘Tradition’, The Journal of American Folklore, 108.430 (1995), 395–412 (p. 396).

[2] Christina Civantos, Between Argentines and Arabs: Argentine Orientalism, Arab Immigrants, and the Writing of Identity (SUNY Press, 2006), p. 17.

[3] Ángel Rama, Writing across Cultures: Narrative Transculturation in Latin America, ed. & trans. by David Frye (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012), p. 23.