The inception of my project to create a digital intertextual edition of MS. Canon. Ital. 243, Pedro de Medina’s (1493-1567) Libro de cosmographía (1538) was rather fortuitous. As a MPhil student in the Palaeography, History of the Book, and Digital Humanities course convened by Professor Henrike Lähnemann, I was expected to select a manuscript or early printed work to study. The plan was to examine the maps of Spanish cities in Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1572-1617) atlas — the digital edition of which I had previously analysed for my undergraduate thesis on visual hybridity in sixteenth century Spanish imperial cartography. On a whim, one dreary fall afternoon, I requested MS. Canon. Ital. 243 alongside the Civitates collection in the Mackerras Reading Room. That aimless decision would allow me to escape the confines of my room in a Hillary term spent in lockdown as I reimagined the cosmos as understood by a man who would become one of the most-renowned Spanish cosmographers. Traversing Ptolemy’s oikoumené towards the New World, that aimless decision would chart the course of my first year at Oxford.

As a branch of knowledge, cosmography comprised the study of the natural world and encompassed the modern disciplines of astronomy, meteorology, chronology, and geography. In the words of historian of science, Maria Portuondo, in sixteenth century Spain, cosmography was a “secret science” or imperial secret due to its inextricable ties to vulnerable Spanish territories in the New World and so work published in the field was heavily censored and rarely disseminated in printed form.[1] Manuscripts like Medina’s are therefore important artefacts of 16th-century Spanish scientific knowledge. And yet, in comparison to his printed works—the Arte de navegar (1545) which boasted over twenty different foreign editions and its subsequent abbreviated form, the Regimiento de navegación (1552 and 1563) — which earned him diffuse acclaim as a cosmographer, Medina’s unpublished works have generated little scholarly interest. Poring over the particular use of technical and theoretical language transcribed in an elegant black hand, I was motivated for my digital edition by a personal desire to understand how this manuscript, which started Medina’s career, has been so overlooked by historians of science.

The last time Medina’s manuscript was taken as a serious object of study was in 1972 when historian Ursula Lamb printed a black-and-white, facsimile edition and English translation entitled A Navigator’s Universe, to broadly negative critical reception. The assessment by critics, and indeed even Lamb herself, was that Medina’s ‘lack of descriptions of new phenomena or hypotheses has overshadowed his contribution to teaching methods and concepts which created the possibilities of progress.’[2] One critic even goes so far as to question, ‘whether a text of this sort is worth publishing in facsimile’ when it omits any ‘geography or discussion of the extent of the known world, subjects which were frequently included in other cosmographies of the period.’[3] Undergirding this assessment is the notion that Medina’s work lacks the hallmarks of scientific modernity when it fails to reference the New World and how its discovery challenged classical models. To borrow a concept from Dr Ayesha Ramachandran, the maestro of the Libro de cosmographía was no ‘worldmaker’[4] — unlike other mid-to-late sixteenth century works, Medina’s failed to imagine a world beyond the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic models that had endured throughout the Middle Ages. However, as showcased in my hypertextual edition, Medina’s universe is not as static as critics presumed.

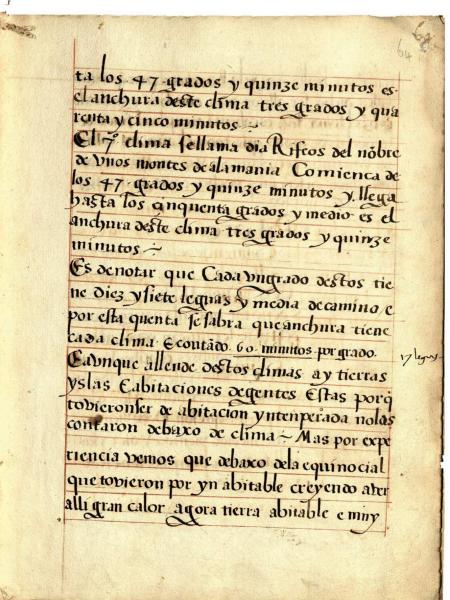

My digital edition of the manuscript integrates a coloured facsimile side-by-side with a modernized xml transcription with hyperlinks that explicate Medina’s numerous disregarded modifications to classical/medieval texts. It shows how Medina uses the idea of ‘experiencia’ or experience to work outside the scope or authority of the classics. Rather than directly contradict Aristotle, Sacrobosco, or Ptolemy, Medina’s cosmography borrows concepts from their works and corrects their applications. Medina’s corrections draw from his contemporaries’ ‘experiencia,’ or knowledge of the newly-conquered Indies, and appears to be a forerunner to the later seventeenth century understanding of the term as it relates to empirics. This challenges the manuscript’s critical reception by illustrating both that its adherence to classical models is not purely medieval and, that as early as 1538, Spanish scientific texts had begun to valorize experience as a metric for science— an often-cited hallmark of scientific modernity.

This digital edition of MS. Canon. Ital. 243 lays the groundwork for further research into the development of the notion of ‘experience’ in early to mid-sixteenth century Iberian works and is the basis for my current research supervised by Dr Alice Brooke. In dialogue with Ramachandran’s concept of ‘worldmaking,’ I argue that while scholars have identified the development of ‘experiencia’ in Spanish science during the latter part of the sixteenth century as part of a humanistic wave across Europe, we can trace the appearance and multiple usages of this word in manuscripts dated earlier than the Relaciones geográficas (1579-1585) conventionally used to mark the advent of more empirical science. By expanding our guide to the navigator’s universe, my digital edition aims to provide the reader with multiple avenues towards more heterogenous perspectives of scientific modernity.

[1] Maria Portuondo. Secret Science: Spanish Cosmography and the New World. (University of Chicago Press, 2009), p.7-8.

[2] Ursula Lamb. A Navigator's Universe: the Libro de Cosmographía of 1538 by Pedro de Medina (The University of Chicago Press, 1972), p.5-6.

[3] ‘Review Notices: A Navigator's Universe. The Libro de Cosmographia of 1538 by Pedro de Medina. Translated and with an Introduction by Ursula Lamb,’ Journal of European Studies 3, no. 1 (1973): pp. 100–101.

[4] Ayesha Ramachandran, The Worldmakers: Global Imagining in Early Modern Europe. (University of Chicago Press, 2015), p.6.