It’s hard to know where to begin when talking about my four months in Moscow. My experience living there was so different to anything else and anywhere else I had lived before that sometimes it feels difficult to put it into words that will do it justice. While I can’t speak for anyone else and the ongoing diplomatic and political tensions between the UK and the Russian Federation certainly leave much to be desired, what I can sincerely say and share with everyone is that my time in Russia was a dream. In fact, looking back on it now with a few months of hindsight, I felt more like a character in a book, like I was living out the ultimate fantasy, instead of a real person in real life.

Moscow has an undeniable charm. Its atmosphere and architecture are something that simply cannot be reproduced. A fair number of western and central European cities and villages have a similitude to them that means when passing through, it makes it hard to distinguish one from the other. Moscow is different. There is something standardised about it: everything is very neat and practical and it’s clear that every building has a preordained function that it carries out with a purpose – we probably have the Soviet Union to thank. But this regularity is in no way detaching nor dehumanising. With Moscow being the first real capital of Russia as well as the reinstated one after the fall of the Russian Empire, it’s an inherently Slavic city. And so, as a fellow Slav (half-Slovak), Moscow with its authentic Slavic spirit engendered the kind of warm and fuzzy feeling I only get when seeing my mum again after a long period of separation. In other words, stepping outside for the first time to wander the Moscow streets and neighbourhoods felt a lot like returning home.

But that’s not to say that there weren’t some things that I had to adjust to. The roads, for example, were terrifyingly wide with about four lanes in each direction, so every time I attempted to cross the street, I would inevitably break out in a nervous sweat out of fear that even though I clearly had the right to walk I would end up as roadkill. This feeling only really started to go away after two months, and after I realised that there were often underground pedestrian tunnels you could take to get to the other side free from vehicular confrontation. Such tunnels can usually be spotted thanks to some mauve-coloured marble that looks a lot like a three-sided box on the pavement. Alternatively, metro stations often have a similar underground passage that can be used without needing to enter the actual station or platform itself.

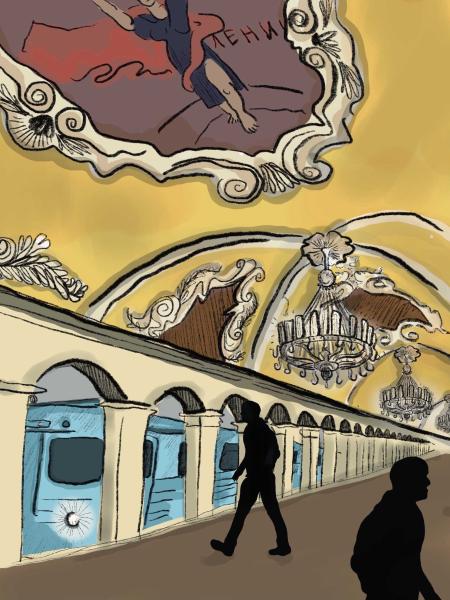

A rather more positive thing I adapted to was the Moscow metro. There aren’t enough adjectives that are synonyms of ‘beautiful’ that can fully capture my love for it; the Moscow metro truly is beautiful in all senses of the word. It is simply glorious: the facades of some stations resembled opera houses or theatres instead of an underground; the bronze or cast-iron names of each station were fixed to the walls, sometimes marble, of the trains’ tunnel; chandeliers or grandiose lamps illuminate the platforms; colourful mosaics, paintings and statues welcome you in and wave you goodbye as you board the train. And I’ve only covered the aesthetic beauty. Trains arrive constantly one after the other (I maintain it’s impossible to be late in Moscow), markers on the platform floor indicate which carriages are less likely to be packed… Finally, not only is there excellent service both at the platform and inside the trains, but all the carriages come equipped with charging outlets and free WiFi.

Every journey around Moscow was impressive to say the least. Not only because of the kilometre-long escalators that carry you out into the light of day, nor the wide streets, but the very ambiance of Moscow itself demonstrated an acute awareness of its historical and national importance. It was perfectly normal to see Soviet-style murals painted on the side of buildings, as much as it was to always have at least one Orthodox church in your line of vision wherever you found yourself. And in fact, this proved to be an advantage of the massive roads: when combined with the distinctive colours and spires of orthodox churches, the imposing height of repurposed Soviet skyscrapers, and the grandeur of beloved landmarks, it meant that from certain regions, it was possible to see clearly all the way across to the other side of central Moscow. The Moskva River was certainly an aid to this end, with its clear waters that would capture the sun setting over the reflection of music halls on the opposite bank.

With such a backdrop, it is no wonder that the Russian intellectual is still very much alive. During my time as an intern translator this was something that I became all too familiar with. My work primarily entailed translating documents and articles from Russian into English for international bookfairs that the Institute for Literary Translation attended as Russian emissaries and often as honoured guests. This meant that I was suddenly extracted from the very classical curriculum of Russian literature which I love and with which I was familiar and plunged right into the heart of the contemporary Russian literary scene. I was translating speeches for former ministers who were opening certain events at these fairs, I was translating interviews with writers who are at the forefront of the new generation of Russian authors, I was translating author biographies, blurbs of books, projects for the future, all of which gave me a new perspective on my degree.

It was mind-blowing to see just how much of an impact 19th- and 20th-century authors have on the new generation of literary pioneers. It was great to see how national languages of the Russian Federation, such as Tartar, and their cultures are finally being given a literary platform to express themselves and share their experience, to learn about the existence of organisations that actively encourage and support literary creation in this field. And of course, it was the cherry on the cake to be working with such an amazing and welcoming team with whom I not only had many intellectual and literature-based discussions, but who really were my family away from home. They would give me advice, recommend places in Moscow to go and see, pick me up if I was feeling down, and helped combat the solitude that was very easy to fall into as a young woman living completely by myself and doing a job that required a lot of withdrawing into oneself. As a translator, you often need silence to fully comprehend not just the meaning of the words on the page, but the nuances of the words, the real sense and message of the sentences that are equally important to convey in your translation. Therefore, it was a real blessing to have such a wonderful family who were always ready to help, who were always up for a chat about anything and everything.

It was thanks to them that I had access to some incredible national events like the televised centenary celebrations for the Library of Foreign Literature with eminent translators, writers, journalists, and the Minister of Culture in attendance. Thanks to them I got to meet writers and journalists as they stopped by the office and talk to them about their latest projects, or observe as they stepped out for further (no doubt) intellectual discussion in the November snow over a cigarette. My colleagues introduced me to Russian caviar, old 80s and 90s Russian rock songs that now feature on my permanent playlist. They were truly the ones who made Moscow magic.

It seems inherently natural for me, therefore, to view Moscow as a very literary city, and not just because the average price a book in pounds was around £4. Thanks to my team at work and my Romantic imagination, I can’t see Moscow as anything less than a literary haven. I made friends with students at the university Oblomov attended. I got to meet my favourite Russian author, hear her talk about her books, and even have a conversation with her. I visited Patriarch Ponds in the August sun with my newly procured hardback copy of Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita sketching the lido and the pond itself in anticipation of the appearance of Woland and instead made a friend who I’m still in contact with today. Moscow, for me, was not just the capital, or a home for my Slavic soul, or my place of work, or literature’s heart, but also a city of inspiration. I wrote a lot and found myself again in my writing. But Moscow inspired me to do much more than that.

That’s not to say that Moscow was all fun and roses all the time. There were occasional problems with my documents, I had some strange neighbours while staying in my AirBnB studio, I almost got mugged by a gang during a really rather pleasant afternoon in August, there was a partial regional lockdown across the county. Four months was not enough time spent in Moscow, and what with my time limit and the complications owing to the pandemic there were still many things I’ve yet to experience – Russian theatre, the Russian ballet, for example. But what I did experience makes me eager to return; the food, the galleries, the zoo, and the people all have me pining for Moscow.

Neither Moscow nor St Petersburg are representative of the majority of Russia and life in the provinces, and unfortunately, I didn’t have time to discover this for myself. But what is certain is that is very refreshing to find myself so removed from the bubble of Oxford and the comfort that it represents with a guaranteed society of people your age, the luxury of paying by battels, and the lovely porters who are so instrumental to ensuring our safety and the smooth-running of colleges. Which is not to say that I don’t miss Oxford. Finding myself suddenly face-to-face with the shock and harshness of real life was something which sometimes got me down. But I found Moscow such a positive and enriching experience that I simply can’t wait to return to my second Slavic home.