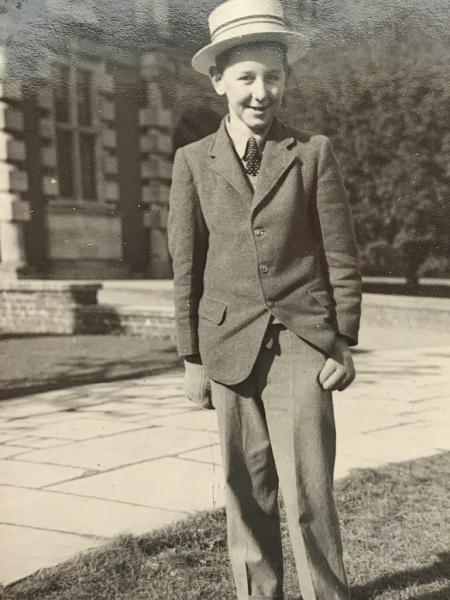

I’d had a restless childhood: born in India, two years in Peking, one year in Hong Kong, before I got back in 1939 aged nine to the UK and went to prep school. All my memories were of abroad. After six years of war when you couldn’t leave the country, I wanted to go abroad again.

In August 1947, very soon after the war, my French teacher at Winchester knew a well-to-do family in a chateau near Vendôme who wished to send their 16-year-old boy to England during the summer holiday and have a boy the same age back on an exchange. He approached me. I had at least 2/3 weeks in France for two summers in a row, staying with Arnauld de Tallencé in Chateau de la Fredonnière at Par Mondoubleau. When I asked what could I bring, the parents said: "More than anything else we would love a tin of Maxwell House coffee." I went better. I bought two – powdered, in sealed tins. They went into ecstasies on my arrival. This was the first real coffee the family had ever had since 1940.

None of the de Tallencé family spoke English; Arnauld spoke a little, which I tried to improve. It was my first encounter of a country house. We ate at a large table, tapestries on the walls, surrounded by a lovely park. The food was marvellous, as I wrote in a letter home. "One can buy a pound of grapes or peaches for a shilling. Huge melons cost about 3/6. It is lovely to be able to buy a dozen large peaches and eat them all in five minutes." I’d never encountered salad being served separately as a course. And wine with every meal. And wonderful cheeses, which we hadn’t had in England.

The other thing in immensely short supply was petrol. Arnauld’s family had a pre-war Citroen with a running board and a hood that let down, and completely bare tyres – because there was no rubber – so you didn’t drive far. When you found a pump, it was all hand-pumped, which you pulled backwards and forwards, like a water pump, and there was a meter which measured it. I don’t remember any tarmac road, they were all dirt track. The local families used a pony and trap. They were like characters from Proust in the passages I later set my French students at the École Normale Supérieure to translate into English. The Marquis de Lussac, the Marquis de Fayet, the Comte d’Harcourt who was to have married the Duchess of Kent when she was Princess of Greece. He was interested when he heard I was hoping to go to Oxford because he had been there for a year himself. These lines to my parents give a flavour: "Drove through Montoire where Pétain met Hitler, to a chateau, 18th-century, in middle of thick woods, owned by Marquis General de Brantes, father killed by the Germans at Dachau. Lunch was a terrifying affair, the table overloaded with cut-glass decanters and whatnots. Arnauld and I on a motorcycle to visit friends who are descendants of Napoleon. Tennis on a cement court with a racket with most of the strings going. Today driving over to Vendôme for fete commemorating liberation. There are nothing but fetes in this part of the country."

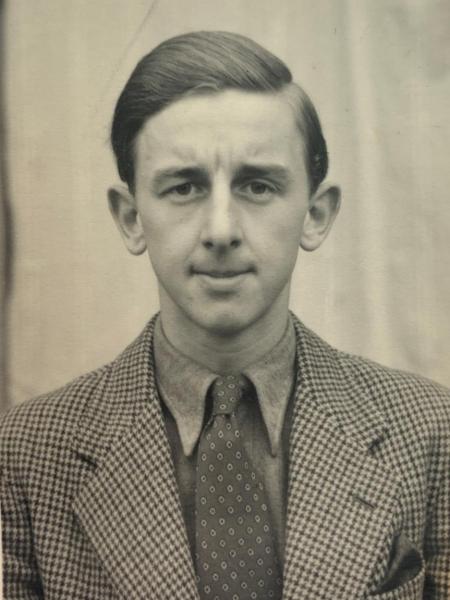

I took the entrance exam to Oxford, to Trinity, and won a scholarship in Modern Languages. I had also been learning German, at about the time when all the atrocities were coming out, but I was able to dissociate Belsen, Buchenwald and all the other horrors, from the German language.

I was the only Wykehamist reading Modern Languages. Otherwise, all the young men had gone off to fight, and a lot of them never came back. The war had lasted for six years and the university had half closed down, and the dons at Oxford were very old and unremarkable. Food rationing was in force until my last term.

I can’t remember a single one of my friends who did Modern Languages except David Cornwell, later John le Carré, who was two years younger. He was reading German, but we went to different lectures. A bit like David, I had succumbed to his wish-washy idea that "the decision to learn a fresh language is an act of friendship." I was thinking of Arnauld and the wonderful time I’d had. But I soon discovered otherwise.

At Trinity, there were four or five Modern Languages students, with 30 to 40 in lectures. The standard of the lectures was not high. If you read French, you didn’t go beyond Gide in the early 20th century. I wrote an essay once a week to my tutor at Trinity, a dreary man called Riccard; then in my last two years, a lovely New Zealander, Frank Barnett.

Unlike English or History, there were hardly any outstanding figures in the Modern Languages faculty. One of the few names to be conjured with was Enid Starkie, a 19th century specialist who had written books about Rimbaud, Baudelaire and Gide. In the only lecture I remember, she told us how she had managed to persuade the university to give Gide an honorary doctorate. When he was in Oxford for the ceremony, he asked Starkie if he could see the Oscar Wilde Room at Magdalen. Starkie took him there and Gide, in ecstasy, went round the room kissing every wall.

I knew Enid Starkie personally when I returned to read for a B. Litt after I’d gone to the École Normale for a year. She became my supervisor. Her rooms were just off St Giles, on the first floor, opposite the Eagle and Child, and she was often to be seen in "the Bird and Baby", as Oxford slang called it, wearing her Breton beret and trousers. As a post grad, I had to decide with Starkie what the subject of my thesis would be. I was interested in one particular early symbolist poet, Jules Laforgue, who I was thought was wonderful. T.S. Eliot was a great admirer, and Philip Larkin. Enid said: "That would be very difficult because I’ve already decided that I am going to write a book on Laforgue." So that kyboshed that. In fact, she never did write it.

Maddeningly, if I’d been allowed to do my B. Litt. on Laforgue, I might have stayed on to become a don at Oxford and spend the rest of my life teaching French literature, which was my dearest wish. So I had to choose someone else. I chose a late 18th-century poet from Dijon called Aloysius Bertrand, who wrote a famous book of prose poems Gaspard de la Nuit, very dark and gloomy and gothic. He was my second choice – because he’d influenced Baudelaire to write Petits poèmes en prose. Starkie had already covered Baudelaire. She thoroughly approved, because it got me well away from the symbolists. But I couldn’t get into Bertrand. I’ve come across notes I took. Oh, what a waste of my life.

One thing: Starkie spoke appalling French, and most of the lecturers spoke French with excruciating accents. I thought this very strange. I thought I was going to learn and improve my French while reading Modern Languages, but not a bit of it; it was all Old French and philology, which was perfectly useless. Nor did we ever speak French to one another.

I was still doing my B.Litt., which I gave up shortly afterwards, when in March 1956, as a result of my experience of reading Modern Languages, I was asked by the editor of The Times Education Supplement, to respond in an editorial to a critical government report. The Civil Service Commissioners had selected practically no one who read Modern Languages for the Foreign Office, and wanted to know why. It caused quite a stir. Of 1,007 modern language students who sat the exams from 1945 to 1954, only 145 had passed – 14%. I myself had been one of the failures.

Perhaps because of my failure, I wrote an excoriating leading article that began: "There is something seriously wrong in the teaching of modern languages in this country. The truth is, however unpalatable it may be, that the best undergraduates at Oxford do not read modern languages. It is far better to go to France to learn French than to study it in vacuo at the Taylorian Institute, Oxford." I was a pipsqueak who wrote this. Even so, it provoked a flurry of letters in support, and only one or two from angry dons. The article went on: "It is to Oxford, if anywhere, that all signs point to the need for reform." Anyone could still get a respectable degree, I concluded, if they had "a parrot-like knowledge of the philological tables and a capacity for the unthinking absorption of the literary values and judgment of others." What was needed was a change in the syllabus, with more emphasis on the history, philosophy, economics, sociology and geography of a country. I had based this recommendation on my post-graduate experience in Paris.

Possibly the most important result of my three years at Oxford was the chance to go the École Normale Supérieure. Every year, an undergraduate who had just taken their BA in French went either from Trinity College, Dublin or Oxford, as a lecteur d’Anglais. After Finals, I was put forward by the Department and was seen at All Souls by the Marshal Foch Professor, Jean Seznec. Samuel Beckett had done it before the war, and there was a lecture room named after him. I had no preparation. I didn’t know Paris at all. I slept in a very comfortable modern hospital-like block in the Rue d’Ulm, a quarter of a mile from the Sorbonne.

The gap between those French I had met with Arnauld, aristocrats living a way of life that appeared to be unchanged, and subsequently those I met at the École Normale, was so huge that they could have been two different nations, two people. The 200 other students were mainly ardent Communist, the first I had met, incredibly bright, among the most brilliants youths of that age in France; all those I knew went on to become teachers at lycées and universities. Serge Doubrovsky, inventor of "auto-fiction" and winner of the Prix Médicis, whose father had been chased out of Russia by the Czar’s police in 1912 for Communist activities; André Authier, a pioneer in X-ray diffraction; and Roger Chazal, who spent 14 years writing a book on Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Another friend was Albert Denjean a peasant from the Pyrenees, who was involved in a Communist cell that met for monthly meetings in a back room of a café in the Latin Quarter with the connivance of the owner; the police got to hear of it and warned him, so he’d have his monthly meetings in the École. I wrote to my parents: "I suspect he sees in his friendship with me a possible chance of making another convert to the Faith! He has promised to let me know in advance when any trouble is brewing, so that I can be on the spot with a camera." It was my first contact with politics in the raw. They were cracking the heads of students in riots with batons. Communists from the École Normale were the first to go out and riot. The police were brutal – trained by Nazis, of course. Hence Maurice Papon, who ended up in prison years later.

Going to a place that was intensely political was an experience totally different to Oxford. The most we had at Oxford was the Oxford Conservative or Labour Club. We were profoundly bored with politics, even David Cornwell didn’t appear to be very interested. I never came across him in the Taylorian, and only discovered later he was spying on us for our political sympathies.

France was nervous by contrast; during the year I was there it was becoming hopelessly embroiled in Indo-China, and single-handedly trying to fight off the Vietminh. In my last few weeks, Dien Ben Phu was surrounded and fell; I remember the headlines in Le Monde. After the fall of France, this was the second humiliation France had suffered. It was the end of empire and quite possible that France would succumb to the Communists. It was a real hothouse atmosphere.

The Second World War was still a huge shadow in the background, the humiliating defeat, the German Occupation. Serge Doubrovsky was sleeping with a loaded pistol under his pillow up until only a few months before he met me, haunted by fear from the war. His father was a tailor who made clothes for German officers, but because he was a Jew they wouldn’t allow him to touch them with his fingers when he measured them. Since he was a very good tailor, he survived at least the first years of German Occupation, before he went into hiding. He told me how a friendly policeman came round and said: "You’ve got to get out quickly, in half an hour my colleagues will be around to arrest you," and how his family were hidden by a couple out in Le Vésinet and couldn’t open the window or draw curtains for two years.

Serge sought me out because he wanted so much to practise and improve his English. If we did a lot of things together, we could speak English the whole time. An "anarchist and impassioned believer in free-love, who is, I feel sure, destined to do great things in the literary world," as I wrote to my parents, Serge did teach me the most wonderful French slang, the so-called contrepétrie. David Cairns, the prize-winning biographer of Berlioz, became fascinated by these obscene puns after I introduced him to them. I remember one. J’ai trempé ma botte dans votre citerne. As a contrepétrie, this becomes j’ai trempé ma bitte dans votre Sauternes. Serge asked me to translate one of his novels, about a wife who commits suicide. I had to give up after a dozen pages as I found it untranslatable into English. I don’t think it was ever translated. I kept in touch with him until his death.

That year I spent in Beckett’s footsteps was the one of the most useful and enjoyable experiences of my life. I have lived on it ever since. I wrote about it as a journalist on The Times when covering the Algerian war, and I made the most of it as a diplomat by claiming to be a former "caiman" at the École Normale: in Paris, where I began my diplomatic career as Private Secretary to the British Ambassador and met General de Gaulle several times; in Cambodia, where I became quite close to Prince Sihanouk (who spoke admirable French). He was very impressed. I went round with him for a week on a tour of South-East Asia where he thought he could settle single-handed the confrontation between Britain and Indonesia. And in Morocco, where I was British Ambassador to King Hassan, who was bilingual in French (Bordeaux University).

Almost the best story arising from my time at the École Normale was when I was at the Paris Embassy and was the secretary of a dining club called Les Misérables which had been set up by Duff Cooper, the first British Ambassador to France after the war. It was intended to bring together leading members of the British and French resistance. Ironically, one of the most respected members – before his true colours emerged – was the Prefect of Police, Maurice Papon, whose armed gendarmes had brutally attacked my fellow students on the Boule Miche with truncheons and kicked them as they lay upon the ground.

Another member was the future President, Georges Pompidou. At one dinner of Les Misérables, I found I was sitting next to Pompidou, then a director of Rothschild’s Bank, and I discovered talking to him that he was a Normalien, and as is the custom with Normaliens the moment you know, you immediately Tutoyer.

At the end of the dinner, Baron Phillip de Rothschild came up to me. "You were speaking very good French, but perhaps I could give you a friendly word of advice, you only Tutoyer if you are very intimate with someone."

"Oh yes, I know that, but I am an honorary Normalien."

There were no other Normalien diplomats in the Foreign Office.