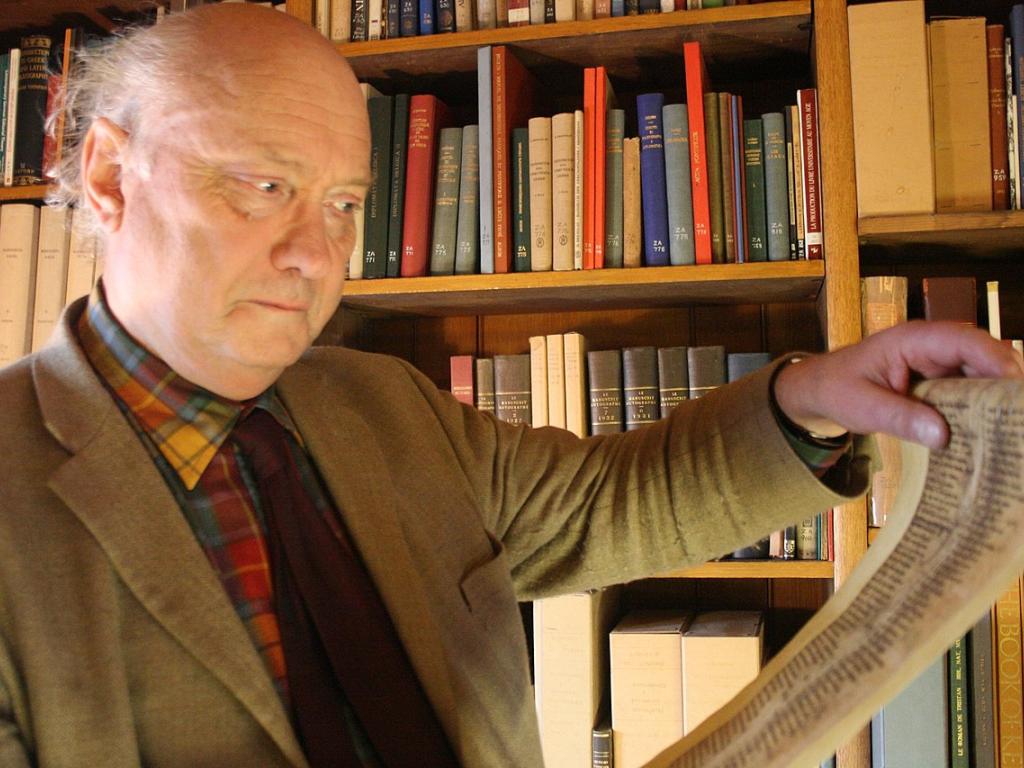

Nigel Palmer, who has died aged 75, shaped the experience of an entire generation of students of medieval German language and literature at Oxford. He first came up to Oxford as a student in 1965 to read German at Worcester College, and was appointed to a lecturership at the University of Durham after just one year of doctoral study in 1970. Having completed his thesis while in full-time academic post in 1975, he returned to Oxford in 1976 as Fellow in German at Oriel College. He moved to St Edmund Hall in 1992 upon his appointment to the University Professorship in German Medieval and Linguistic Studies, from which he retired in 2012. If anything, retirement enabled him to work even more intensively than he had done before, and he was a firm fixture in the academic life of his field, and in Medieval Studies at Oxford, until the very end of his life.

It is as a tutor and supervisor of graduate students that most alumni of the University will remember Nigel. He was immensely supportive, firmly engaged, and those to whom he offered his tremendous expertise and wise counsel, which he did freely and generously, far exceeded those for whom he was formally responsible. His medieval German graduate seminar was an institution, and much treasured. The standard was resolutely professional. Several doctoral theses had their roots in topics first encountered through that Wednesday morning seminar, and many journal articles started life as papers first given there. Participants had to tackle texts and subjects well beyond the confines of their own particular research interests, opening their eyes to new fields of study and approaches in a shared endeavour of learning and discovery. The emphasis was very much on the ‘shared’: Nigel was as much a fellow participant as any of his students, and hated academic grand-standing. That was often in evidence at conferences, where he was a real friend to younger scholars and students, especially to those accustomed to the stricter hierarchies of institutions abroad. He was firmly resistant to the idea of the academic Festschrift. His was an active commitment to inclusivity long before the word had entered the realms of academic policy.

Nigel understood his academic position as a stewardship of his subject, and felt a deep responsibility to ensure that it should thrive. During his tenure Oxford advanced to a position of international standing in the study and scholarship of the language and literature of medieval Germany. He considered himself responsible for the languages spoken and written in the medieval German lands – Latin, German and Dutch – in equal measure. These were to be encountered in the forms in which they had been transmitted from the Middle Ages, in manuscript and early printed book. Nigel was one of the foremost experts in the world not just in his primary field of medieval German studies, but also in medieval Latin literature, and (especially) in codicology, the study of the manuscript and early printed book. His methodological contribution was to bring the accumulation of detailed evidence to bear upon intellectual questions of wider significance: to take disciplines like palaeography, codicology and philology beyond themselves, and so to extend the boundaries of human knowledge. He did that in a deliberate and conscious manner that sought to overcome the division in Germanophone scholarship between the ‘auxiliary’ disciplines (the so-called Hilfswissenschaften) and academic research proper. The latter should not exist as an abstract pursuit undertaken in ignorance of the former, but equally the former should not remain merely at the level of description.

The body of scholarship that Nigel published in the course of his academic career will long remain as the foundation on which all who work on those subjects henceforth must build. He wrote for specialists, often on recondite topics, but always in an accessible manner, whether in English or in German, such that to read his books and articles is a pleasure both aesthetic and intellectual, and always fundamentally instructive. His is a great loss to scholarship, but will be most keenly felt in his home, in Oxford, to the colleges and libraries of which he was so deeply committed.