‘An inaugural lecture’, Karen Leeder began, having ascended to the podium in the Main Hall of the Taylor Institution on 11 October 2022, ‘is a strange beast, a genre in and of itself’. The large audience which had gathered to celebrate her appointment as the new Schwarz-Taylor Chair of German Language and Literature witnessed this solemn occasion, which signified the continuing life of a more than century-old professorship. It was a particularly poignant moment in that this internationally important and prestigious Chair of German has now been secured for future generations of scholars by a most generous donation from the Dieter Schwarz Foundation. While marking the importance of tradition, however, Professor Jonathan Thacker, Chair of the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, emphasised in his introduction, the inauguration also signalled the start of something new, as Leeder is both the first woman and the first scholar of contemporary literature to hold the prestigious post. While paying tribute to those who came before her, Leeder thus also outlined new accents which she will introduce during her tenure.

With Durs Grünbein, she chose to lecture on a contemporary German poet who, for his part, has had a deeply conflicted relationship with the traditions which shaped him. His volume of poetry on the Allied firebombing of his hometown Dresden during the Second World War, which was published in 2005 and recently translated into English as Porcelain: Poem on the Downfall of My City (Seagull Books, 2020) by Leeder herself, testifies to this ongoing contestation, and it addresses a highly controversial episode in Germany’s public memory. For Leeder’s purposes, too, the Dresden poem appeared a demanding subject. Even as she took up a professorship which, as she emphasised, ‘is and always has been about furthering Anglo-German connections’, she challenged her audience to grapple with the violence which has been an undeniable part of the two countries’ past relationship and to question the ethical imperatives which arise from such contested histories.

This enquiry is at the heart of Grünbein’s own work. He reassesses the victim-narrative which has dominated German memories of the devastating bombing in February 1945, utilising the guiding image of the porcelain that has embodied Dresden’s historical self-consciousness. A source of tremendous pride to the city and to Germany at large, the fine, white material produced by the famous Meissen manufacture was coveted by Europe’s royalty, but it also served as an heirloom for ordinary families, becoming a visible marker of intergenerational transmission. The devastation of the city, then, quite literally shattered these treasured legacies. For many Germans who lived through the War, it marked the beginning of a nostalgic longing for lost national wholeness, enabling the propagandistic instrumentalisation of the bombing as an act of ‘terror’ inflicted on an innocent civil population. This narrative, Leeder noted, was taken over almost seamlessly from the National Socialists by the new East German government, which denounced the bombing by the Western Allies as an act of capitalist imperialism. The myth’s impact, however, was felt well beyond the borders of the GDR and past its demise in 1990, as it continues to be mobilised by the German far right to this day.

Grünbein’s poetry, the lecture outlined, utilises the image of broken porcelain to respond to this political overdetermination. The fourth of the poems, cited by Leeder, connects the shattering of the porcelain under the Allied bombs with the glass which shattered during the so-called Kristallnacht, the violent pogrom against Germany’s Jewish population in 1938: ‘Porcelain, endless porcelain was ground to dust […]. But not just that. Ach, once upon a time – the faintest / tinkling, then across the crime scene the thunder rolled. / Not a rowdy wedding-do. It was “The Night of Broken Glass”’. Connecting the two symbolic breaking points, Porcelain recalls that the German civil population had helped unleash the Second World War and participated in the perpetration of the Holocaust prior to the bombing, and concludes: ‘What’s that? Innocent? Disgrace came long ago.’

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these poetic strategies provoked controversy. Notably, Grünbein, who was born in 1962, was attacked for commenting on events which predated his own birth and passing judgement on traumatic experiences which were not rightfully his own. The poem’s form, too, became a bone of contention. Its elegiac tone and apparent classicism, critics alleged, risked romanticising, fetishising, historical violence, inserting Porcelain into longer-standing debates on the legitimacy of poetic language in a post-Holocaust world. Crucially, however, Leeder argued, Grünbein’s critics have tended to overlook that the poem is preoccupied with staging these very conflicts. The poetic persona is the first to highlight the limitations of his post-memorial vision as a ‘Johnny-come-lately’ to Dresden’s history. The authority of his perspective is relativised in a densely intertextual work, which engages interlocutors ranging from the post-Holocaust poet Paul Celan to the German-Jewish scholar Victor Klemperer, a survivor of the Dresden bombing. This process of self-reflection, moreover, is embedded formally. Breaking with its classical aspirations, Porcelain’s metre repeatedly stumbles, its rhymes alternate with half- and missed rhymes. The porcelain which is at the work’s thematic core may thus be understood as a conceptual metaphor for Grünbein’s poetic process. The poem continues to gesture towards the beauty of the artefacts which leave the Meissen workshops in pristine condition but also traces the life of these objects until – and indeed beyond – the moment of their destruction, producing a fragmentary aesthetics which incorporates moments of rupture, rather than glossing over them.

Porcelain, Leeder’s lecture concluded, may be understood through the Japanese art of kintsugi, in which broken pottery is mended with gold-laced lacquer. In 2019, Edmund de Waal commissioned the artist Maiko Tsutsumi to use this technique on a set of porcelain plates from the Klemperer estate. These items, which had belonged to the same Victor Klemperer referenced by Grünbein, were seized as NS authorities expropriated Jewish citizens, before being fire-blackened and broken in the 1945 bombing. Incorporated into De Waal’s ‘Library of Exile’ exhibition, which later travelled to the British Library, the kintsugi porcelain signals wholeness, its loss, and a process of restoration which highlights an object’s troubled history while creating something new.

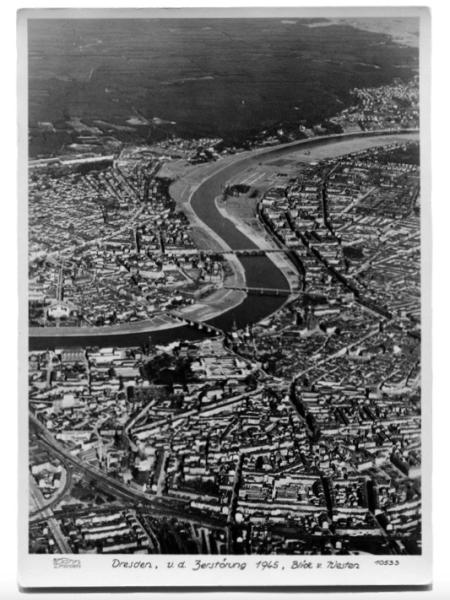

Kintsugi, then, may also stand for Leeder’s own contribution to the ongoing life of Grünbein’s work, her translation and scholarship having allowed Porcelain to resonate beyond an at times claustrophobic national arena. Auslandsgermanistik, especially in the United Kingdom, appears to have a unique role to play in the reappraisal of contested cultural memories. In his 2019 Oxford Weidenfeld Lectures, Grünbein recalled that when he arrived in London by plane, his imagination superposed the Elbe and the Thames. The aerial view he adopted ominously recalled that of the bomber planes dispatched during the era of the two cities’ violent enmity – and yet, the likeness of the two rivers’ shapes also suggested a sense of connection between two apparently disparate lieux de mémoire. A transnational perspective, which is embedded in institutional exchange and exercised in the practice of translation, may therefore help reimagine the very notion of tradition as an act which entails not only looking back but also looking across and towards history’s others. In highlighting this perspective, Leeder’s inaugural pointed to the challenges and aspirations of her tenure of the Schwarz-Taylor chair. At a time of war in Europe, instability and renewed tensions in Anglo-German relations, it demonstrated that a meaningful connection with the past and adequate understanding of the present entail an awareness of the painful breaking points inherent within them. Only then, it appears, can tradition retain its legitimacy, making the continued review of institutional structures, historical narratives, and cultural forms an integral part of Modern Languages teaching and research in the United Kingdom today.