Twenty-five years ago, you could count on one hand the number of scholars who had heard of Marie Krysinska (1857–1908). And yet, this Polish-born writer (of 3 collections of poetry, 3 novels, dozens of short stories, essays, and librettos) was among the most prolific, if not important, writers of the 1880s and 1890s, and one of the few women in an otherwise male-dominated cultural space. Fast forward a few decades later, my colleague Florence Goulesque and I are co-directing Krysinska’s six-volume Œuvres complètes, with a dozen scholars collaborating on every aspect of her publications. The first volume includes critical editions of her first two collections of poetry: Rythmes pittoresques (1890) and Joies errantes (1894).

As we explain in our introduction, these two collections tell the story of Krysinska’s first steps in French poetry: setting to music other poets’ verses and publishing some of her own, often in Le Chat noir, the weekly publication of Rodolphe Salis’s cabaret by the same name. She interrupted her poetic activity in the early 1880s when she and her husband, the painter Georges Bellenger, took their honeymoon in the U.S.; while she was away (particularly in mid-1886) the literary magazine La Vogue published the first modern free-verse poems written in French. The furore surrounding this nouveauté passed over some not insignificant details: Arthur Rimbaud had written ‘Marine’ and ‘Mouvement’ before he left Europe in 1875, and Krysinska’s own poems from the period 1881-3 suggested a very clear departure from the conventions of verse poetry. Upon her return to France she argued — repeatedly, strenuously — for her rightful place among the verslibristes: both in Rythmes pittoresques, which collects her previously published poems and which includes a word attesting to her ‘innovation’, and four years later, in the preface she wrote to Joies errantes, in which offers a scathing attack on the misogyny that she felt reigned over French poetry of the fin de siècle. She would ultimately be unsuccessful in her claims for la ‘maternité’ du vers libre: never receiving credit during her lifetime — xenophobia and anti-Semitism also played a role here — she died forgotten and penniless in 1908.

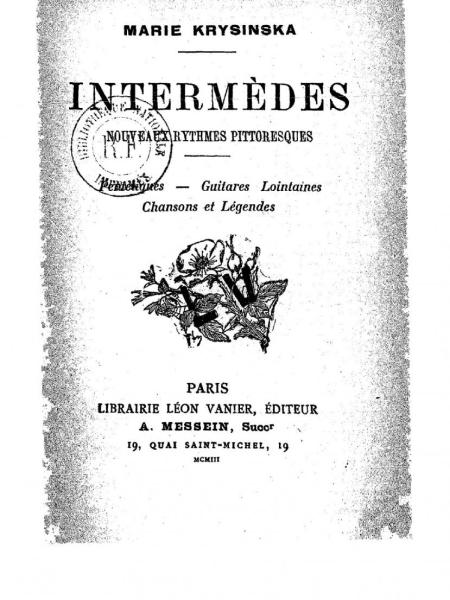

Modern-day readers will find much of interest in the recently published first volumes of this series, devoted to her final (and much longer) poetry collection, Intermèdes (1903/4). Krysinska’s poems offer a fluidity and departure from poetic conventions; a musicality to her language (evident for example in her repetitions throughout a poem, as phrases in certain lines as well as refrains); and an early reconsideration of female figures from the Bible and Greek and Roman mythology. She would later be a regular contributor to Marguerite Durand’s feminist publication La Fronde, and her essays will be published in a later volume of these complete works. For the novelty that she brings to both content and form, and for her role as one of the first poets to experiment with free-verse poetry of the 1880s, Krysinska’s poetry — and, as subsequent volumes will show, her novels, short stories, and music — deserve a fresh look from twenty-first-century readers.

Marie Krysinska, Œuvres complètes, dir. Florence Goulesque and Seth Whidden. Section I. Rythmes pittoresques. Édition par Seth Whidden; Joies errantes. Édition par Yann Frémy (†) (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2022).

and

Marie Krysinska, Œuvres complètes, dir. Florence Goulesque and Seth Whidden. Section I. Intermèdes. Édition par Darci Gardner et Laurent Robert (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2022).