Academic jobs are certainly never boring, and the culture of intensive dialogue and often instant response which characterise intensive term-time periods can be difficult to balance with the very different pace required for equally intensive scholarly writing. Research leave can therefore be a welcome opportunity to focus on reading, study of archive material, and writing, and I was fortunate recently to spend a month at the university of Freiburg. While our research has benefitted from the rapid transition towards online materials necessitated by the pandemic, we have also come to appreciate how special face to face meetings are. The period in Freiburg was therefore a wonderful opportunity to re-connect with colleagues with whom I have collaborated over the years, and also to see manuscripts ‘in person’, which is quite different from studying two-dimensional images.

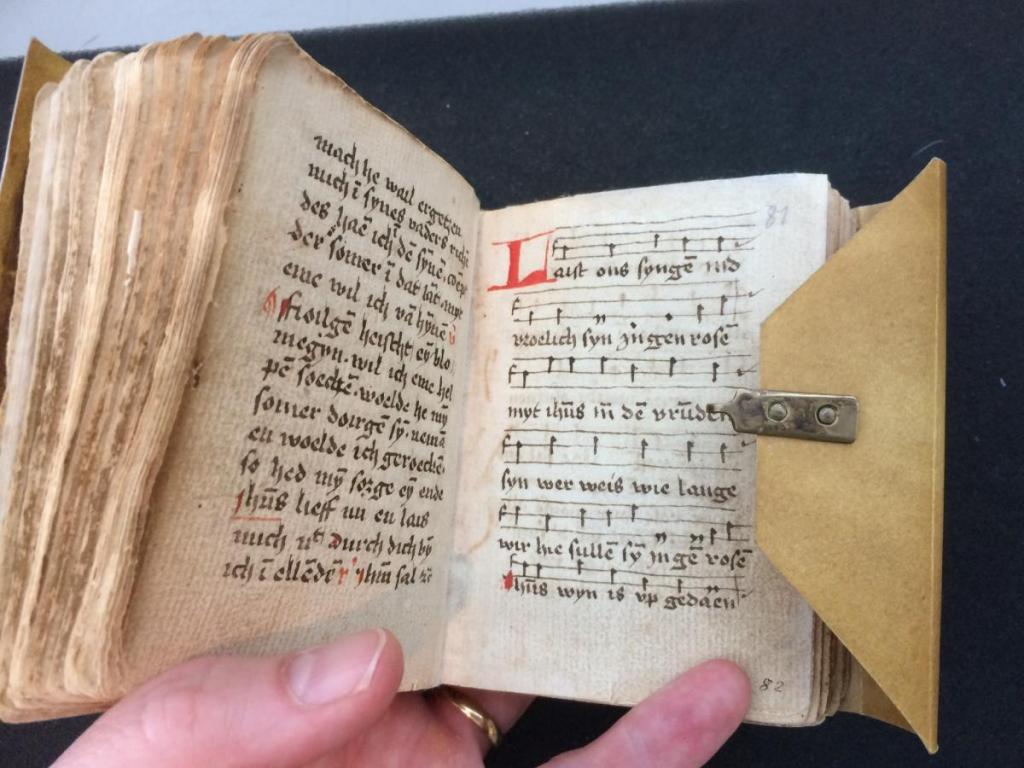

Freiburg is a special place for medievalists, because so much of the medieval history of the city and region is still tangible. Popular imagination often focuses on castles, but the many convents in and around Freiburg are at least as important, because they were places of learning and study as much as contemplative communities. My current research on late medieval religious song highlights the importance of song as a means of mediating between learned theology as discussed at the universities and urban religious practices transposing such knowledge into experience. We have evidence of this not just from the songs themselves, but also from documents which can give us a sense of the context in which the singing of vernacular religious songs may have taken place: many of the Dominican convents in Freiburg and the Alemannic region chose to record the spiritual life of their convents in so-called ‘Schwesternbücher’(sister books), and they often highlight the special significance of singing for the nuns. In Freiburg, some of these manuscripts survive and can now be consulted in the university library or in digitised copies – but it is also possible to have lunch in buildings which once formed part of one of the Dominican convents, the so-called Adelhaus. Handling the manuscripts is a reminder of how tactile and object books can be: their small scale is evident from the measurements given in a manuscript description which is part of every digitisation, but that abstract knowledge is quite different from actually holding one of these small-scale books which can be cradled in one hand, clearly precious to their owners even if they are not lavishly illuminated or ostentatiously large. What the physical object reveals is instead part and parcel of the content: just as the songs are an adaptation and translation of speculative theological knowledge into something which can be experienced by the individual singer, so the material objects encourage the singer or scribe to hold the book in her hand, carrying it around and feeling a tangible connection.

The convivial meetings with colleagues and graduate students were also a vivid reminder of how much academic work relies on a sense of community. Often, the informal, casual, unplanned conversations are the most creative moments. In Freiburg, these informal lunchtime meetings and workshops with graduate students were therefore a wonderful opportunity to try out a new topic – ways in which post-human approaches and ecocriticism can be made fruitful for medieval studies, while also providing new perspectives on contemporary issues. Reading Hildegard of Bingen or Konrad von Megenberg’s ‘Book of Nature’ with students often sparked lively discussion and highlighted that pre-modern texts and their non-binary ways of seeing and representing the world may at times help us to probe contemporary tendencies to create binary oppositions. Such informal exchanges are vital at all levels: undergraduates from Freiburg and Oxford get to experience life in a different academic culture during their Year Abroad exchanges; our annual graduate colloquium gives the graduates a chance to present their research to an international audience, but in a friendly and informal setting; and to me, mentoring post-docs from German-speaking universities when they spend time working in Oxford is a wonderful way of ensuring that such connections between academic cultures are strengthened, that a sense of community is kept alive even if political narratives favour islands.