By Olga Smolyak

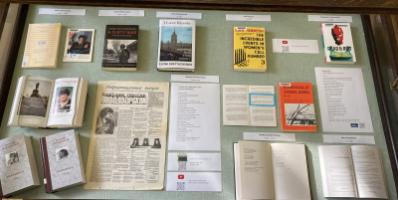

The idea of a book exhibition about women’s political activism in Russia came to me by chance, as many things tend to do. A year ago, I was at work in the library when a big pile of new books arrived. One of the books surprised me. It was a Russian copy of The Incredible Events in Women's Cell Number 3 – a novel by Kira Yarmysh based on her own experience. The novel is related to the nationwide protest demonstration ‘He’s Not Our Tsar’ organised by Alexey Navalny’s team ahead of Putin’s inauguration in May 2018. I had been following the news from Russia and remembered how Yarmysh – Navalny’s spokeswoman – was arrested and sentenced to 25 days for disseminating information in preparation for the protest. And now I was holding her book describing the time she spent in prison. This fact gave me the feeling that my news-scrolling habits were being visited by the materiality of Russian protests.

Books are present in our lives as material objects by taking up space on shelves or bedside tables. Some of these books are just commodities: we enjoy reading and leave them covered in dust or throw them away. But others have significant meaning to us and are transformed, following the Russian philosopher Ekaterina Degot, from being tovar (commodity) to becoming tovarishch (comrade). The book by Kira Yarmysh made me think about my compatriots who left Russia because they were against the war. I thought that many would like to read it as a way to cope with the challenges of being far from home. The book made me also think about an attempt to demonstrate to a wider audience the legacy of the dissident movement in Russia and how this tradition continues.

I narrowed my focus to women’s activism and made this choice for a specific reason. Women’s history is a topic in my own research. At the time when I met Yarmysh’s book, I was finishing my doctoral thesis on the construction of public discourses about women’s roles in the USSR in the 1960s-1980s. There I present the media representation of women’s roles at work and at home as both dynamic and eventful, despite the widespread characteristic of the era as one of ‘stagnation.’ Literature and films paid less attention to the fact that women had to combine full-time jobs with family duties. They were instead focused on the glorification of ‘woman’s destiny.’ In journalism, the relationship between women’s roles at work and at home was a familiar theme, and the explicit recognition of the ‘double burden’ revealed a wide range of opinions. However, as I show in my research, the authorities exercised a significant level of control over what was sayable and who was speaking. It was, for instance, impossible to question the approach of the official media to the ‘woman question.’

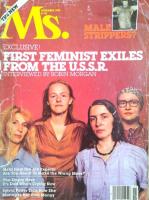

The history of the volume Woman and Russia, presented in the exhibition, demonstrates the hierarchies of voices in Soviet public discourse. The volume was made and disseminated by the first feminists in contravention of Soviet censorship in 1979. Although it fitted the agenda of the ‘woman question’ as it was represented by Soviet media, there were differences in emphasis and detail where the feminist manifestos were concerned, notably, their direct blame of the Soviet regime for the social conditions of women, and their frank narratives about the inhumane treatment of women in natal clinics and in prisons – places that had been pushed far beyond the margins of Soviet public space. These differences did away with any possibility of publication in official Soviet media. Indeed, the result of the collection’s samizdat appearance was a political crackdown on the authors of Woman and Russia. The Soviet secret police (KGB) seized most of the journal’s copies and put the authors under surveillance. On the eve of the Moscow Olympics, in 1980, they were formally expelled from the Soviet Union. This fact received wide international attention for instance in journals such as Ms. Magazine – the first American feminist magazine. They published an interview with this group and put them on the cover. Before being expelled from the country, Natalia Malakhovskaya and Tatyana Goricheva reacted to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. They issued an anti-war appeal to Soviet women when they called on mothers not to let their sons go to war, emphasising that three years in prison for refusing military service was better than a shameful death.

Anti-war appeals and protests are two things that activists have had in common before, during, and after the regime of the Soviet Union. In 1916, Aleksandra Kollontai wrote the most striking anti-war feminist text Who Needs War? In the 1990s, Valeriya Novodvorskaya, Galina Starovoitova, Anna Politkovskaya, whose works are presented in the exhibition, were vocal against the war in Chechnya. Anna Politkovskaya started her career as a journalist in 1982 writing on social issues but later changed to writing investigative reports on the Second Chechen War (1999-2005). In her articles, Politkovskaya described abuses committed by Russian military forces, Chechen rebels, and the administration led by Akhmad Kadyrov and his son Ramzan. She authored several books about the Chechen wars before she was murdered in 2006. The person who ordered the murder has not yet been named, and one of the killers, recruited to the Russo-Ukrainian War, received a pardon from President Putin in November 2023.

In the same month, the artist and musician Aleksandra (Sasha) Skochilenko was sentenced to seven years in prison for replacing price tags in a St Petersburg supermarket with anti-war messages criticising Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This is not the first such criminal case in Russia against artists, in which the act of creativity itself becomes a reason for repression. 10th March 2024 marks the third trial of theatre director Evgeniya (Zhenya) Berkovich and playwright Svetlana Petriichuk. They were detained in May 2023 as suspects in a criminal case, charged with ‘justifying terrorism’. The reason for the criminal case – and the arrests – was the performance of the play Finist the Brave Falcon which was staged in 2020. This documentary-style play tells the story of Russian women recruited through social media to join radical Islamists in Syria under the pretext of romantic relationships. In the spring of 2022, the play received the national theatre award Golden Mask for best costumes and Svetlana Petriichuk got the best playwright award.

The books, poetry, and artworks in the exhibition represent personal stories of feminists and political activists who have been persistent in dealing with the following three issues: the right to be a citizen, the defence of human dignity, and the emancipation of women. These materials further guide us towards a wider historical experience as they speak of the limitlessly inventive cruelty of the Russian authorities, coming down on those who protest against state militarism, corruption, and the disregard for human rights. From this perspective, the exhibition, although focused on individuals, brings Russian women’s history into an international context.