‘I believe in the visits people make in each other’s lives […]. I believe that there is life-giving energy there’, says Dimitris Papaioannou to Stella Mastorosteriou. I read these lines in the brochure distributed at the foyer of Sadler’s Wells in London, which I bought minutes after the last scheduled performance of Papaioannou’s hyper-visual dance-theatre show INK had finished, on 2 March 2024. Forty-eight hours later, 4 March at 5pm, Dimitris Papaioannou, indeed, visited us at Oxford and this time he generously shared the floor with the audience of a packed Main Hall at the Taylorian, Dimitris Papanikolaou, Marcus Bell, Zoë Jennings, and me for a public discussion.

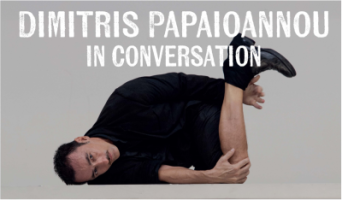

Dimitris Papaioannou is an avant-garde performer, choreographer, director, painter, comics creator, and designer, catapulted to the epicentre of (inter)national fame and recognition especially after creating the Athens 2004 Olympic Games Ceremonies. His latest works have been welcomed with enthusiasm by audiences all around the globe, resulting in sold-out runs for both his large spectacles and his intimate pieces, such as The Great Tamer (2017), Since She (2018), Transverse Orientation, and, most recently, his duet with Šuka Horn, INK, which premiered in 2021. However, I had never met Papaioannou, nor had I seen him perform on stage before – he hadn’t done so since 2012. In INK, I was confronted with: a laminated, flooded scene; a device spraying water; lights exploding into reflections onto the pitch black backdrops; some ordinary props, ropes, toy fishes, a disturbing baby doll, a bowl, a disco ball, circus pieces – objects that could be found in a flea market animated and repurposed; an eclectic playlist of songs, their eerie sounds, and a turntable; inhabiting and emerging through this setting, the bodies of Papaioanou and Horn, the latter mostly in absolute nudity, hunting for, escaping, finding anew, succumbing to, and wrestling with each other. Into what sort of experience have I been immerged within this corner of Sadler’s Wells, this engulfing deep water, this expanding and expansive stain, this weird and arousing darkroom? Papaioannou’s affectively and sensorially fraught enchainment of performance acts seduced me, excited me, pleased me, just to simulate to tame and dispossess me; exhibited dominance only to have the joy of letting me turn the tables, ensnared me only to relish in my slipping away.

‘If dance is an architectural motion in space, then, yes, I am a choreographer’, Papaioannou told us. Prompted by Marcus, Papaioannou glossed over his hybrid performance art, unsettling expectations and shying away from clean-cut classifications, in terms of reactivating norms and their moulds as the very means to manage to leak through their cracks. If there is a history and a repertory of expressive languages for what has been culturally coded and established as choreography, ‘I make use of this language [of dance/choreography] just to admit that I am not speaking it, because I am speaking it’, he says. Drawing on his early training as a painter, Papaioannou gives rise to arresting visual sequences to negotiate the very loosening of what can be felt as a forceful grip, an interplay between command and its suspension that seems to stand at the heart of hearts of the latest phase of his career. As he informs us, it is not anymore about creating storyboards which performers will populate, that is, a story of control from beginning to end, but the shows are created processually, through performing improvisations on an initial idea with his team. A conceptual reconfiguration whose transformative dimension is, intriguingly, dovetailing with his presentations of bodies, as he replied to Zoë. In Papaioannou’s works, the complete, singular body segues into fragmentation only to be recomposed by parts belonging to many. A metamorphosis through regrouping and rearranging which is the making believe not solely of a fact, but more of a procedure, involving time, eros, and a stretching towards the spectator, meeting and inserting them into the assemblage. For, Papaioannou adds, thanks to an attendee’s follow-up question, it is not only the visual illusion of the body dismembered and collectively reconstructed, but the spectator’s imaginative and affective investment that actualises this redrafting and suturing of plural embodiments.

The beginning of the event was spurred by a screening of an edited version of Primal Matter (2012), a video recasting the ‘entire work in seventeen minutes’. When asked about this transfiguration of a performance piece into, and his broader preoccupation with, video art, Papaioannou cheekily replied he is a ‘closeted’ film director and a ‘passionate editor’: ‘Editing is a form of choreography’, he says, lingering on how it informs his oeuvre and its dissemination. From this optic, I start pondering on how Papaioannou’s work might not only think with (and materialise) aesthetically and affectively potent images, but also with an underlying cinematic logic. Lest I provide an erroneous answer, I wonder instead why I stay riveted to this turn to editing: to a praxis arguing on the possibilities of processings, sequencings, reorderings, collations; its affordances for coalitions, solidarities, and resistance. In the guise of conclusion, I would like to dwell on two moments when my cognitive, affective, and bodily responses took an editorial spin, tethered to Papaioannou’s tangential, proximal cultural presence.

* Drenched and dressed in black, Dimitris Papaioannou is on stage, pounding on the floor what seems to be an octopus – again and again. A cut and a flashback to my summers in the peninsula of Chalkidiki, Greece. Me with an all-male company (my dad, neighbours, and other children), fishing and diving; catching an octopus, throwing it repeatedly on the ground to make it soft; muscles swelling and relaxing, again and again. A protoqueer awakening of homosexual desire. Is this how men are made?

* 9 March, lying on a couch with my closest friends in the UK, I see videos of a violent mob assaulting a trans* couple in the middle of Thessaloniki, my hometown’s, most central square. I instinctively search for my friends’ hands to hold, to weave our fingers into fists, in a touching linkage stretching to our communities back home. His work featuring at the 26th Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival, Papaioannou commented on the attack the next day, metres away from where it happened.