Academics have a part to play in public debates

University languages departments play a vital role in the educational and professional pipeline that sustains the teaching of languages and understanding of the cultures with which they’re associated.

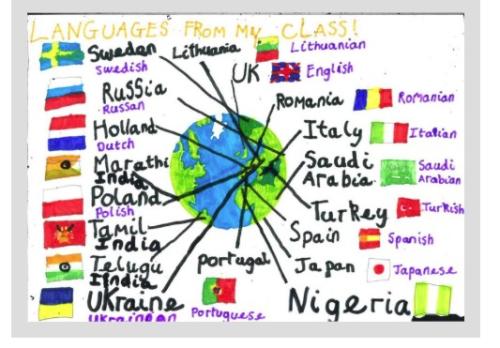

The importance of learning languages other than English can be hard to appreciate in an English-speaking country given the predominance of English in international discourse and media, and the ease with which AI tools can now produce translations in widely used languages. Indeed learning a language can seem dispensable at school – optionality was introduced in 2004 from age 14 and prompted a decline in take-up for GCSE and A level that is still ongoing. This impacts on the pipeline right through to training teachers, supplying experts with the language skills needed in business and diplomacy, and educating agile communicators who are equipped to wield soft power in the international arena.

Faculty members are not only experts in specific languages and research areas – we also form a vital part of the educational fabric of the subject, and as such we’re well placed to contribute to public debate on the value of languages, help shape public policy on languages, and act as advocates for the whole breadth of the subject. Increasingly, it’s becoming necessary for us to develop our antennae for policy developments and foster contact with teachers, head teachers and policy makers in order to respond to policy developments and trends, understand the challenges, and identify opportunities for strengthening the subject both nationally and within our own university and colleges.

Critical areas of policy engagement

Faculty members can play an important part in keeping the Faculty in touch with government policy concerning qualifications in the secondary sector, and depending on opportunities, they may contribute to syllabus design and debates around assessment. In 2015, the Faculty contributed to securing the future of GCSEs and A levels in community languages such as Polish, Panjabi and Turkish when they were threatened with abolition by exam boards. Faculty members were also involved in the design of the A level syllabus introduced for first examination in 2018 by the university-led A Level Content Advisory Board (ALCAB) and the DfE-led design of the GCSE in MFL introduced for first examination in 2026. Such processes are invariably complex, must take account of diverse interests and constraints, and may have non-ideal outcomes from the perspective of a university department, but engagement is invaluable in making the voice of universities heard, contributing to policy initiatives, and helping to sustain dialogue across sectors.

Every new government brings new or modified policy priorities, and it’s important for us to keep our ear to the ground in the context of change which may impact our subject. The current Labour government launched a Curriculum and Assessment Review (CAR) in July 2024, which may result in some abolished or modified policies, policy shifts and new initiatives concerning provision for languages in schools. The Faculty submitted a response to the review on the basis of its perspectives and concerns while also drawing on helpful consultation with subject associations, head teachers and MFL teachers. The Interim Report published on 18 March indicates an approach of ‘evolution not revolution’ and the final report will be published in autumn 2025. The Faculty will assess in due course to what extent any policy changes may directly or indirectly affect recruitment for Modern Languages.

An ongoing issue is the matter of ‘severe grading’ in Modern Foreign Languages both at GCSE and at A level, with which Faculty members have engaged since 2013 in collaboration with Modern Languages associations, head teachers and MFL teachers. This concerns the statistically slightly lower grades awarded in MFL in relation to comparable subjects, contributing to the perception of the subject as difficult, and at worst impacting on take-up, progression, and provision for the subject in schools. Policy engagement in this area remains important but needs to take account of the immense complexities facing Ofqual in addressing an anomaly that ultimately goes back to the O Level era, given that grading changes are constrained by the principle of ‘comparable outcomes’ between years. Policy successes, which involved Faculty participation, include Ofqual’s implementation in 2017 of a one-off upwards grade adjustment designed to account for the advantage of native speakers. In 2023–24 grading was made slightly more generous in GCSE French and German in order to bring standards into line with Spanish. But further adjustment is needed.

Opportunities and challenges of diversity

A key characteristic and value of Modern Languages as a discipline is its diversity, investigated and showcased in the Faculty-led research project Creative Multilingualism funded by the AHRC in 2016-2020. Our Faculty is immensely fortunate in being able to support not only the three languages traditionally taught in schools – French, Spanish and German – but also Italian, Russian, Portuguese, Modern Greek, Czech with Slovak, Polish, and special subjects in Catalan, Galician, Yiddish, Bulgarian/Macedonian, Croatian/Serbian, Slovak and Ukrainian. All languages except for French and Spanish are available from Beginner level. Moreover, we offer languages not just in their modern form but embrace medieval and early modern language, literature and culture. In a very real sense, then, we give access to key areas of global cultural memory through first-hand sources, enabling current students and future researchers to understand the voices that produced those sources, and translate them for others.

That very diversity of the subject however makes for significant challenges in terms of provision and funding throughout the educational pipeline. Modern Languages departments in schools and universities must productively reconcile the distinctive identity of each language and culture with the identity of the subject as a whole; each language with its associated culture(s) needs self-sufficient teaching provision; and the study of a language and its associated culture(s) requires robust teaching of language skills alongside the teaching of analytical skills, essay writing, and knowledge and understanding of the society, history, and culture including literature.

The diversity that is essential to the subject makes advocacy and policy engagement vital – within our own institution, within the educational system, and within society.

Networking and collaborating with our allies

In Oxford we are institutionally, geographically and internationally exceptionally well placed to draw on the resources of organisations in the UK that represent our discipline at all levels and support the cultures and languages we study and research.

The Faculty has a long tradition of productive networking, exchange of ideas and sharing of information about new developments with school teachers at the well-attended annual meetings of the Sir Robert Taylor Society every September. The Faculty’s investment in schools liaison with a dedicated officer and academic director has created an excellent basis for developing advocacy and policy engagement more systematically, also involving the colleges. They play a vital role through admissions and outreach activities. Colleges also collaborate with the Faculty in supporting initiatives with an advocacy and policy dimension such as the Oxford German Network and the Queen’s Translation Exchange.

The British Academy, which includes members of the Faculty among its fellowship, is highly proactive in supporting the subject across sectors through its Languages programme, and it was a key contributor to the landmark initiative Towards a national languages strategy: education and skills, launched in 2020. A further important initiative supported by the BA is the online portal The Languages Gateway, designed to share information about initiatives and activities across languages and sectors. Other important organisations in the policy arena for languages are the University Council For Languages (UCFL) and the schools-focused Association for Language Learning (ALL) and Independent Schools Modern Languages Association (ISMLA). The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Modern Languages (APPG) contributes important position statements and arranges occasional meetings on key topics of concern. The British Council produces the useful annual publication Language Trends England.

Modern Languages is fortunate in being able to draw on resources and expertise offered by the relevant embassies and by cultural institutes such as the Institut Français, Instituto Cervantes, Goethe Institut, Italian Cultural Institute or Instituto Camões. The Maison Française in Oxford offers fabulous opportunities for networking in the course of its rich programme of events. The Portuguese Sub-faculty annually features Brazilian culture during the interdisciplinary events and activities of Brazil Week. The German Ambassador is currently heading the initiative Making the Case for German, which also promotes collaboration more broadly on influencing public policy in favour of sustaining the study of languages in the UK from primary level through to universities.

Policy engagement in Modern Languages will be at its most effective if it builds on diversity as a strength – through pooling of expertise, collaboration with other organisations, and sharing of ideas and resources.