Contemporary scholarship is more and more concerned with crossing boundaries of time, space, and identity. The study of single authors, historical periods and literary traditions has been questioned in a multi-perspectival or, if one prefers, multidisciplinary way. In the sciences and the humanities alike, we are witnessing an epochal change thanks to which we are allowed to think in unconventional, and hitherto ‘prohibited’, ways. In a sense, we are rapidly moving forward yet nostalgically looking back at a time when (or at a space where) ideas, words and numbers were complementary, and stateless.

Boundaries are well-established, and endorsed, as much as they are incomprehensible. My academic work gives voice to this critical paradox in a number of ways: by bringing together, rather than separating, specialisms; by embracing a globalising, transnational agenda; and by bridging the gap between criticism and creativity. This is how, and why, my doctoral thesis – The Diasporic Canon. American Anthologies of Contemporary Italian Poetry, 1945-2015 – considers translated (and ‘migrated’) poetry as an integral part of literary canons, whilst Itaca – a collection of poems that I published in 2016 – explores exile and homecoming as two parallel modes of existence in today’s society. In a sense, Itaca is my doctoral thesis put into verse.

Non so perché ti scrivo, Itaca.

In fondo tutti hanno parlato di te:

la tua voce è sogno che scava fondali.

Loto ibisco fiordaliso datteri mimose.

Città esotica, eppure consapevole,

come il dolore.

Città underground e underhand,

gitana e zingara, come i tuoi pesci.

Ho paura della lingua che parli,

perché tutto ciò che è invisibile, resta.

E se la lingua non si vede e non si tocca,

gli alfabeti restano, come le tombe.

Sembra che tanto più parli,

tanto più diventi straniera.

Mia terra e mio esilio.

Mare pieno di fiumi nascosti.

Non so dare un perché, ma ti scrivo ancora.

I don’t know why I’m writing to you, Ithaca.

In the end everyone has spoken about you:

your voice is a dream digging up ocean depths.

Lotus hibiscus lilies dates mimosas.

Exotic city, yet ever vigilant,

like sorrow.

Subterranean city, city of subterfuge,

wild and wandering, like the sea.

I’m afraid of the language you speak,

because all that is invisible remains.

And if the language cannot be seen

and cannot be touched,

the alphabets remain, like tombs.

It seems the more you speak

the more you become foreign.

My land and my exile.

Sea full of hidden rivers.

I don’t know why, but I’m writing to you still.

(tr. Reinier van Straten)

Since the aim of scholarship is to see things differently and comparatively, sometimes even uncomfortably and antithetically, for most of us to research means to discover. We conduct research to remember the forgotten, to observe the invisible, or to reveal the unknown. At the same time, however, whether we are dealing with a ‘new’ text, methodology or vision of the world, we share an aspiration to renew, and to be new, that is future-oriented. Research, I would say, is an archaeological exercise that cannot exist without its avant-garde, experimental dimensions. This is perhaps why critical perspectives deny themselves, change and, ultimately, return. This is why, I think, a poem about Ithaca and a thesis about tradition(s) can be still worth writing as long as they come back, inhabit, and belong anew.

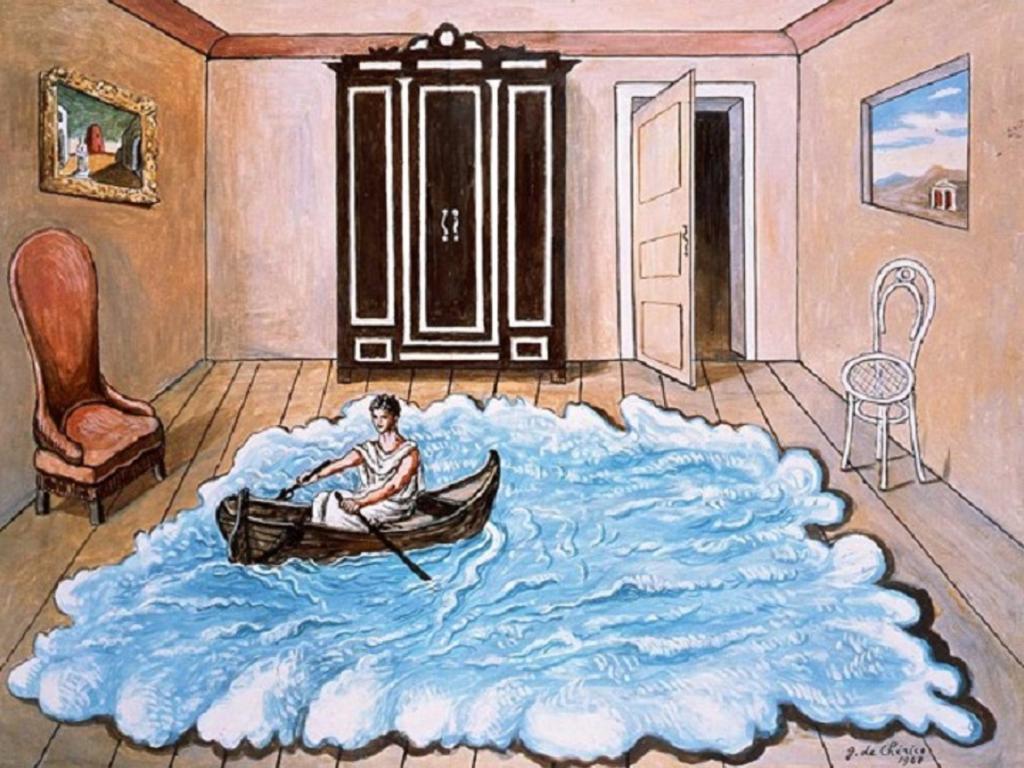

This particular aspect of scholarship – i.e. its temporal and spatial fluidity – made me realise that the act of discovery is not a passive, backward-looking movement, but rather an active, all-embracing form of creation. We tend to find what we are looking for insomuch as we conceive what we have imagined. As researchers, we are authors, architects and creators at once, fighting Ulysses in the midst, and depths, of our rooms; or, at least, this is the way we can recognise ourselves in Giorgio De Chirico’s famous painting. I wrote this poem – ‘Nuvole’ (‘Clouds’) – in the Taylorian Library on one of Oxford’s windiest days, while reflecting on the nature of translation. The Main Reading Room was floating in an ocean of leaves, pages and shaking windows; together with the books, I was caught in an unspoken storm.

NUVOLE

Non so la mia casa che finestre avrà.

Forse le finestre di un volto.

Capitello straniero, zattera d’ombre;

onda delle tende nel sole.

Ma adesso soffiate fumo su tutto.

CLOUDS

I know not if my house shall have windows.

Maybe the windows that make a face.

Foreign city, a raft of shadows;

and the curtain billows in the sun.

For now, smoke blows through everything.

(tr. Stephen Romer)

I research and write (but also dance) in a continuous way. I cannot say what comes first and what comes second. Creative writing and scholarship are two parallel moments of creation, questioning strategies and types of denial. Research happens outside as much as inside my imagination. It does not simply rely on external materials (texts, ideas), but also on spiritual resources. It is the medium that connects myself with the world, but also, more importantly, the way in which the world connects with me. Similarly, creative writing can function as a mode of scholarly enquiry, just as scientific as the most refined critical tools. Few things are indeed as accurate, stringent, almost anatomically reproducible as a book that (re)becomes a woman or a man.

Research is my writing inside out, whereas writing is my research outside in.

Itaca è una persona.

Itaca, sei tu.

Alfabeto sconosciuto,

che non morirai.

Lingua senza fine, eternità

inizi da una parola sola.

Che lingua parlo? Che lingua sono?

Noi siamo pausa nelle lingue di Dio.

Eterna è la lingua con cui mi dono a te.

Ithaca is someone.

Ithaca, is you.

An alphabet I know not,

that you may not die.

Language without end, eternity

issued from a single word.

The language I speak? The language I am?

We are lulls in the languages of God.

Eternal is the language

in which I give myself to you.

(tr. Stephen Romer)

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Stephen Romer and Reineir van Straten for translating my poems, and for giving me permission to publish them. Thank you also to Catriona Seth for believing in my work.

The poems quoted in this article are included in Marta V. Arnaldi, Itaca (Milan: Montedit, 2016). This collection of poems was awarded the ‘Jacques Prévert Literary Prize’ and the ‘Elena Violani Landi Literary Prize’, Centre for Contemporary Poetry, University of Bologna.