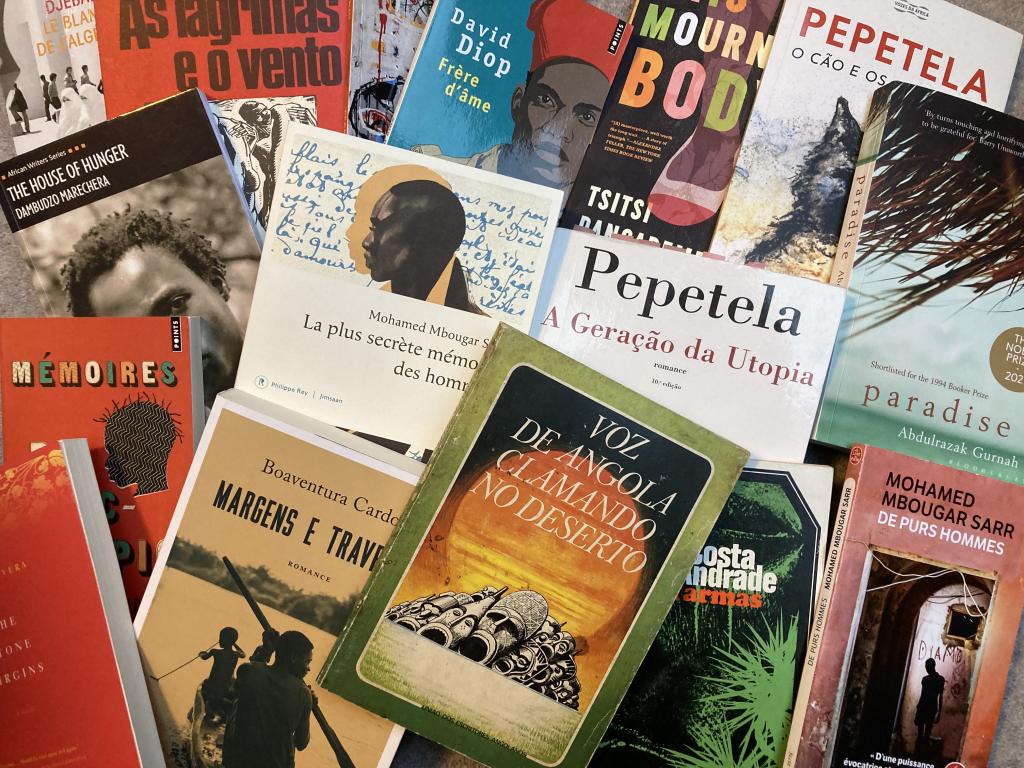

2021 was an exceptional year for African literature. It started in May, when Ugandan writer Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi received the Jhalak Prize for her celebrated novel The First Woman. The following month, Franco-Senegalese novelist David Diop won the international Booker prize for At Night All Blood is Black, while Zimbabwean writer Tsitsi Damgaremgba was awarded not one but two prizes, the Peace Prize of the German book trade and the Pen Pinter Prize for International Writer of Courage. In October, Tanzanian writer Abdulrazak Gurnah received the supreme consecration, the Nobel Prize for Literature. In the following weeks, Mozambican writer Paulina Chiziane was the recipient of the highest literary award for the Portuguese language, the Premio Camões and Boubacar Boris Diop was awarded the 2022 Neustadt International Prize, often called the American Nobel. On the same November day when Mohammed Mbougar Sarr (Senegal) won the Goncourt Prize for the acclaimed The Most Secrete Memory of Men, South African writer Damon Galgut received the Booker Prize for The Promise, concluding an extraordinary season for African writers, anglophone, francophone and lusophone, continental and diasporic, male and female.

In his Nobel lecture delivered in December 2021, Abdelrazak Gurnah mentioned the necessity, when writing, to counter simplistic narratives and convey the complexity of characters and places long maintained under European colonial domination, especially when attempting to retrieve and make sense of traumatic events, such as warfare, displacement or abject poverty. In many ways, his speech echoed the concerns about ‘a single story’ formulated a few years earlier by another African writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Implicitly, both highlighted one of the central themes of Mbougar Sarr’s Goncourt-winning novel, the ambivalence and tribulations of African writers, caught between individual prerogative and collective identities, European literary forms and African cosmogonies, colonial legacies and post-independence disillusions.

How African writers have addressed these challenges, embraced their ambivalence and written counter-histories exposing the biases of European minds and historiographies are central to my current research, supported by a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship at the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and a JRF at Jesus College. Celebrating the aesthetic power of narratives of emancipation and resistance, I aim to acknowledge the revolutionary work of African writers who have transfigured their aspirations for freedom into works of art, and challenged others to follow in their footsteps. Centring African voices in their cultural, geographical and linguistic diversity, my research looks at how writers from Algeria, Congo-Brazzaville, Angola and Zimbabwe have engaged with their respective countries’ histories, particularly narratives of anticolonial resistance and postcolonial civil wars.

In a 1982 lecture to the University of Ibadan, Nigerian literary critique Abiola Irele (1936-2017) spoke about the ambivalent feelings Africans have towards Europe, whose profound influence on African history is steeped in racial and cultural arrogance. Irele noted how this ambivalence created alienation and a divided consciousness among Africans. This is particularly the case for African writers and intellectuals, who have often written in European languages. African novelists have found in European literary forms, such as the novel, inspiring ways to convey postcolonial African experiences. In parallel, they have faced persistent racist, Eurocentric and colonial attitudes in the media, in publishing and in academia.

For Irele, it was imperative that Africans embrace their feeling of alienation and utilise its ‘creative potential’ as ‘a sensitive tension between the immediate closeness of the self and the reflected distance of the other.’ This agenda has been taken up by African artists and intellectuals on the continent and throughout its diaspora, who have offered the world powerful contributions in the arts, performance, literature, and scholarship. Until recently, however, white Western scholarly institutions have failed to listen to, welcome, and echo these voices in their richness and diversity. They have refused to address their historical and personal connections to white supremacy, slavery and colonialism. Similarly, literary analysis of African texts has too often remained embedded in Western theories, methods and disciplines. A more systematic engagement with the worlds, works, and words of African philosophers, historians and feminists, illuminates the epistemological and historical dimension of African fiction, its contestation of global power relations, its inspiring critique of Western modernity, and its crafting of new political and literary imaginaries.

Engaging with African knowledge traditions and intellectual figures can take many forms. African fiction literature has a long tradition of questioning the rigid boundaries drawn between human and non-human, humanity and animality, the visible and the invisible. Analysing African texts through the lens of ecocriticism leads to imagining new coalitions between humans and non-human living elements and to forging new connections with nature and the land. African queer and feminist lenses capture vividly how non-confirming gender and sexual identities are crushed between Western imperialism and African patriarchy, colonial legacies and the phallic gesticulations of African postcolonial potentates. African feminism and its emphasis on solidarity and sorority also raises major issues about the tension between individual and collective identities, masterfully explored in postcolonial narratives of fiction. Finally, the figure of the “griot”, a West African bard and praise-singer, both historian, archivist, performer and truth-teller, is particularly apposite to think critically about the writer as an intellectual, eager to participate in and shape debates on historical consciousness, power relations and collective identities.

The Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1949-2012) argued that “historical authenticity resides not in the fidelity to an alleged past but in an honesty vis-à-vis the present as it re-presents the past. Even in relation to the past our authenticity resides in the struggles of our present.” In their constant efforts to question colonial narratives and postcolonial patriotic histories, to exalt memories of struggles and traumas and to retrieve previously discarded ways of seeing and being in the world, African writers fight epistemic erasure, environmental collapse and exploitative politics. Through their creative mobilisation of African cosmologies and traditions of resistance, their works offer us major sources to understand the contemporary world and imagine another one beyond it.