By Nora Baker

Whilst carrying out research for my thesis on Huguenot life-writing, I came across several memorable characters, one of whom was a Frenchwoman persecuted during her youth. I was lucky enough to uncover the earliest known version of her autobiography which I am planning to publish in an annotated critical edition.

Though she remains to this day a largely unknown figure, Blanche Gamond (1664/1665-1718) built up something of a minor cult following during both her own lifetime and the later nineteenth century. Born in the town of Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux, the daughter of Michel Gamond and Benoîte Malarte was still only in her late teens when French state persecution against Protestant families like her own reached new levels of severity. In 1683, soldiers known as dragoons were stationed in her household, with the intention of intimidating residents into converting to Catholicism. In 1685, King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had allowed for some religious tolerance, and as a result an estimated 150,000-200,000 French Protestants, or Huguenots, fled their homeland to practise their beliefs freely elsewhere. Gamond would eventually feature in this broader statistic, but during her initial attempt to escape to Geneva, she was captured by the authorities and imprisoned for several months in both Grenoble and Valence. Following her release and resettlement in modern-day Switzerland, Gamond wrote an autobiographical account of her experiences, focusing in detail on the beatings she suffered and the bravery she supposedly displayed. While in confinement, she managed to smuggle through some correspondence with her erstwhile pastor, François Murat. He in turn sent a missive of Gamond’s to prominent Huguenot refugee writer Pierre Jurieu, who published the young woman’s words in a volume of his Lettres pastorales, a series of pamphlets printed in Amsterdam and distributed widely among the Protestant diaspora. The publication of Gamond’s story in Jurieu’s tome seems to have raised her profile somewhat within the refugee community; she writes in her longer account that, once she had been freed, she was visited by a number of well-wishers familiar with her story. But it is indeed this longer account that has led to her relative prominence within the field of Huguenot history.

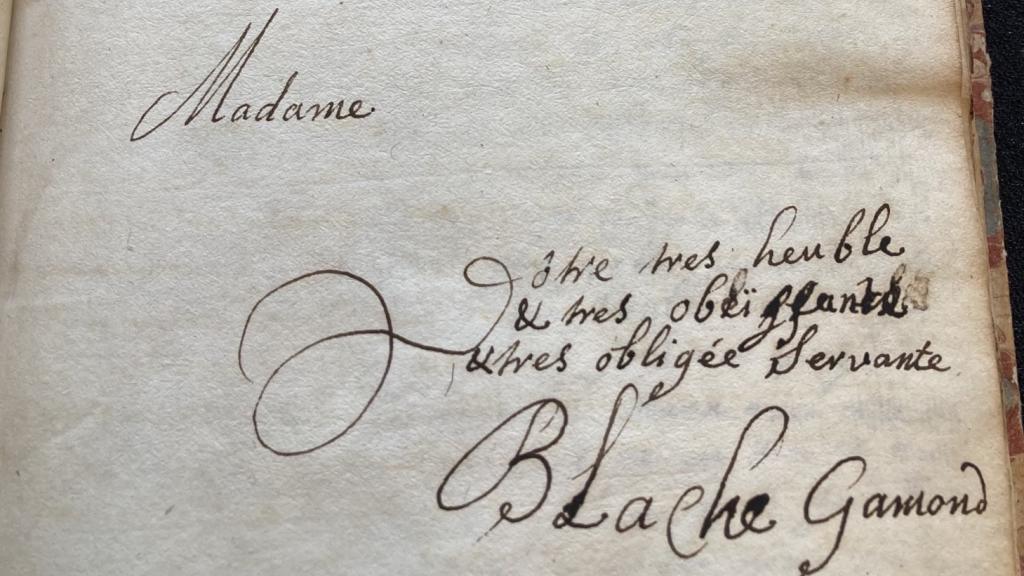

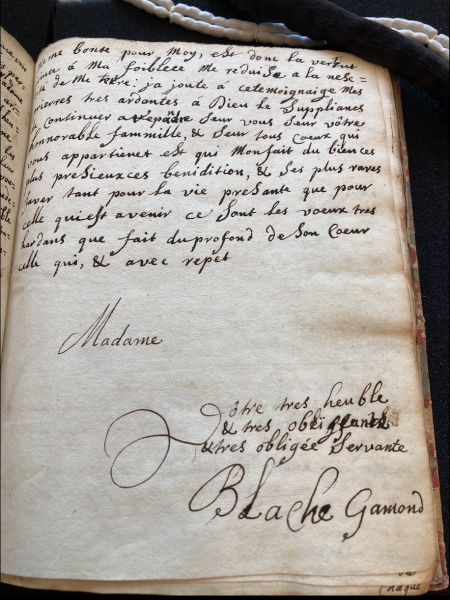

In 1867, Protestant historian Théodore Claparède located a manuscript version of Gamond’s story in the Bibliothèque de Genève (Papiers Court 17/D). He decided to print the text – albeit omitting several instances of what he deemed ‘vulgar expressions’ – in several volumes of the Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire du Protestantisme Français. Claparède also printed a book-length edition of the manuscript in the same year, giving it the title Une heroïne protestante. It is the latter work that most historians and literary specialists have used as a reference when writing on Gamond. In the past few decades, several evangelical publishing houses have also issued their own editions of the young woman’s story, again based on Une héroïne protestante, believing it to be a potential source of edification for their readers. Claparède in fact published Gamond’s text once more in 1880, this time in conjunction with the writing of her erstwhile companion Jeanne Terrasson, under the title Deux héroïnes de la foi. Some amendments are made in this later edition following Claparède’s discovery of a second manuscript of Gamond’s text, at the time in the hands of a Mr Chappuis. This version is currently held at the Bibliothèque Centrale et Universitaire de Lausanne (Collection des Cèdres, TH 929). A few months ago, however, I was able to confirm that neither of these was in fact the original in Gamond’s own hand.

Manuscript S 437, in the Zentralbibliothek in Zürich, has a much longer title than those given to either the Lausanne or Geneva documents, and it is written in a far less certain hand. In the upper left-hand corner of the would-be title page, the word ‘originale’ in written, in fainter ink. Unconventional and inconsistent spellings abound in far greater number compared to the other hand-written versions of the text, as do awkward phrasings which later copyists appear to have deemed it their job to standardize. The Zurich manuscript also features additional details written out of the later versions, such as instructions given by pastor Murat as to how Gamond was to read his letters. MS S 437 is dated “A Berne, ce 15me setambre 1689” [Berne, 15 September 1689]. This contradicts previous scholarly estimates that the original manuscript was created in Zurich around 1688. On the inside cover of the manuscript’s binding, there is the inscription “Pour Benjamin Fa’si. 1691.” Presumably this was Benjamin Fäsi (1633-1701), a writer who had connections to St. Gallen, a town to whose consistory Gamond and her father made several appeals for alms. A German translation of the first couple of sections of Gamond’s account is written out in Kurrentschrift on smaller pages pasted at the back of the manuscript’s binding. Could it be that Fäsi or one of his contemporaries began to render the young Frenchwoman’s story into their own tongue, only to be waylaid by some unforeseen obstacle? The partial translation leaves off just at the point where Gamond describes her group passing by Glandasse mountain during their initial attempt to leave France, though for some reason the German text censors the name of this natural feature, giving it only as ‘Berg XXX’.

Gamond died of oedema, or dropsy, in Zurich in 1718. It would seem that she spent much of her adult life in poverty, as malnutrition is a major cause of oedema, and she is recorded as having made several requests for charity to various bodies in Switzerland following her move to the Confederation. The injury she sustained to her leg during an attempt to escape from a window back in Valence may also have had a severe impact on her overall health. However, she still found it in her to commit her version of her life’s events to paper, though several narrative and paratextual clues hint that she continued to be haunted by the memory of her captivity. While Gamond herself might have relished Claparède’s designation of her as a ‘heroine’, rather than idealize her essence and experiences, it is probably best to consider her for what she was: a woman trying to make the best of the bad situation she found herself in.