By Justin Vyvyan-Jones

I spent my Year Abroad in the medieval university city of Rostock, translating a little-known but deeply fascinating collection of songs known today as the Rostocker Liederbuch. Jotted down over half a millennium ago, it opens a door onto a boisterous medieval world populated by nuns behaving badly, firebrand political rebels, wily old farmers, and glamorous warrior lords. Across my twelve months on the project team, I found how much my experience as a 21stCAD foreign student was overlapping with that of the Liederbuch’s creators. Like them, I was living as part of an international, multilingual community of scholars, experiencing the long cycle of the Baltic year among the brick Gothic spires and city walls of Rostock, the scholarly “Star of the North”. I would like to use this article to introduce you to the amazing and little-known treasure that is the Rostocker Liederbuch, and to share some of my experiences of translating and immersing myself in its world.

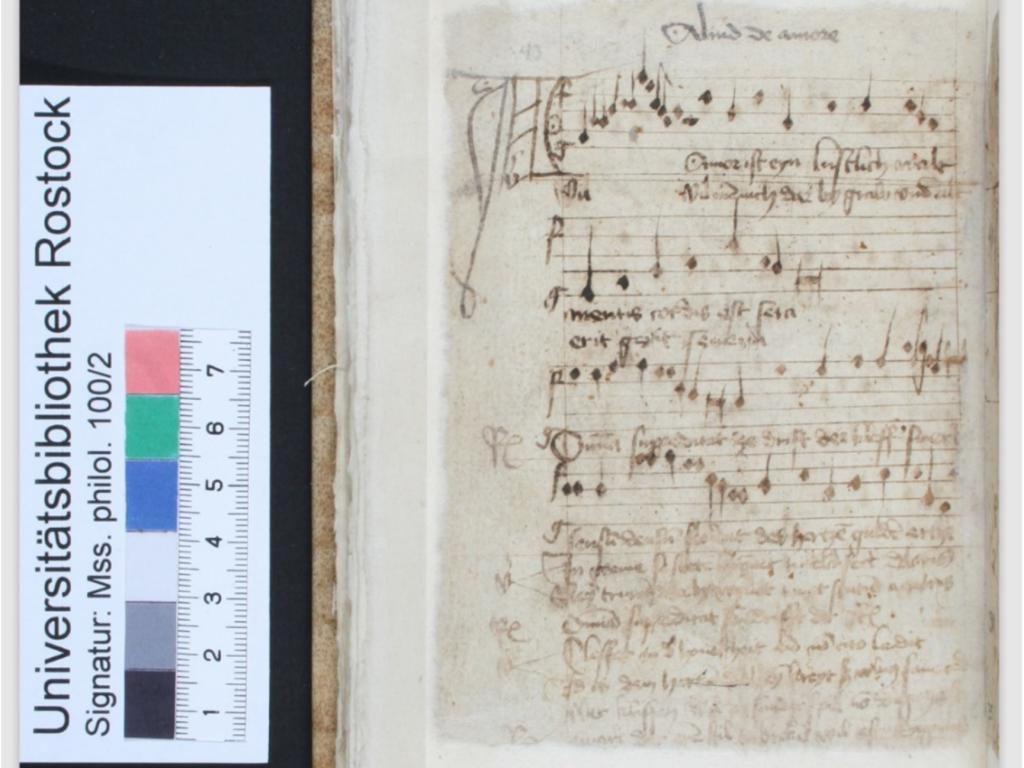

The Rostocker Liederbuch is small and scruffy. Its anonymous compliers were not seeking to create a prestige artefact like the lavish Codex Manesse. Rather, they used (relatively) cheap paper and a succession of dark inks to jot down a staggeringly varied collection of songs – both lyrics and melodies – that were circulating among the internationally-mobile community of their north German university. Inscriptions and signoffs hint at the context in which the collection was compiled: one song is sung “with a three-step dance to the student halls”; various others bear messages from individuals who “gave” songs to the anonymous scribes. These include Brother Steffan, who “gave with great love” a matching pair of Latin and German love-songs; Lord Andreas, an academic “magister” who contributed a South German mealtime hymn; and Johannes and Elizabeth, lovers whose joint signoff fluently mixes German and Latin. Fifty-one songs are noted in Middle Low German, the local vernacular as well as the business language of the Hanseatic League, although many songs bear signs of migration from other areas; seven are Latin; and two are Latin-German bilingual. This diversity reflects the role of Latin as the living language of Rostock’s university community, serving as a lingua franca between the German, Slavic, Scandinavian, Flemish, and British scholars named in Rostock’s matriculation records.

The stylistic and thematic variety of the Liederbuch songs is huge. Previously undiscovered Marian hymns, set to haunting and intricate melodies, appear alongside staggeringly rude ballads narrating the escapades of crafty peasants, manipulative clerics, and insatiably naughty nuns (who extensively quote the Bible in Latin double-entendres). Interminable encomia praise the majesty of Duke Otto the Victorious, the Lion of Brunswick, in an impressively overstretched series of lion metaphors; another song urges Rostock’s citizens to “guard your gates, your barricades and towers!” against a brutal siege. The signoff of this last song is the most detailed self-portrait of a real individual in the whole collection, and a touching reminder of the real lives underlying the Liederbuch’s creation:

He who composed this song

is young in years:

he's well-known in Rostock

(his father sang before the altar)

with blonde, curly hair.

May God be his steadfast protector,

wherever he should go.

His eyes cannot see properly;

his hands bring forth the music

of trumpets and stringed instruments.1

The anonymous young poet’s song is datable to a violent struggle between the city of Rostock and its feudal overlords in 1487AD, which ended in defeat and massacre shortly after the song’s composition. What happened to the young singer is unknown, but his song is the last datable text in the Liederbuch. The next datable event in the manuscript’s life comes in 1568AD, after the generation of young scholars in the 1480sAD would have died. Absent its compilers, the scruffy paper manuscript was cut up and used to bind books for the very dukes against whom Rostock had rebelled. However, 44 pages, bearing 60 texts and 31 melodies, survived legibly within the ducal library’s book bindings. And so it was that Dr Bruno Claussen, librarian of Rostock University Library, discovered a single leaf of the Liederbuch in 1914 while performing conservation work. By 1919, he had extracted and published the wholeLiederbuch corpus, remarking: “The preservation of the Liederbuch, as contradictory as it may sound, is owed to the fact that it was exposed to destruction 350 years ago.”2

My first contact with the Liederbuch came about when Oxford’s Prof. Henrike Lähnemann, my superb medievalist tutor, put me in touch with Rostock’s chief medievalist, Prof. Franz-Josef Holznagel. I was looking for a Year Abroad project where I could hone my newly-discovered skills as a translator of medieval verse; Holznagel was looking for an English native-speaker to produce accompanying translations for his new critical edition of the Liederbuch. I spent a year under his mentorship as we intensively examined each song in turn. As the year went by, I experienced student life in that great medieval city, consciously inhabiting the same spaces that shaped the Liederbuch’s creation. I sang and worshipped in the brick Gothic churches where the Liederbuch’s Marian hymns could have been performed; I recorded a Liederbuch Christmas carol with an Oxford medievalist ensemble. I walked the city’s fortifications, looking out from the city’s east wall where the ducal armies launched their assaults. I made merry with my fellow Rostock international students, dancing many a three-step back to the student halls, and occasionally (for research purposes only) entering the spirit of Song 13:

The morrow, the morrow,

will bring us nought but sorrow,

but evening’s pretty great!

Tonight we’re in the cellar getting smashed;

tomorrow we’ll be badly strapped for cash.

But still, the evening’s great.3

Franz-Josef Holznagel and I exceeded our initial expectations: we translated the entire Liederbuch, and then versified each translated song to fit its original melody. On returning to Oxford, I wrote my thesis on the Liederbuch’s German-Latin bilingual songs, using matriculation records and university statutes to research the role of international mobility and multilingualism in 1480sAD Rostock. This thesis, which gratifyingly carried off the Classics faculty’s thesis prize for Latin Language and Literature, will form the basis for an upcoming scholarly publication. I look forward to spending more time engaging with the Rostocker Liederbuch and the human stories underlying its formation. I feel I’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of this extraordinarily lively collection.

1 RLB 58 s.7, my translation.

2 Claussen 1919, S. III, my translation.

3 RLB 13 s.2, my translation.