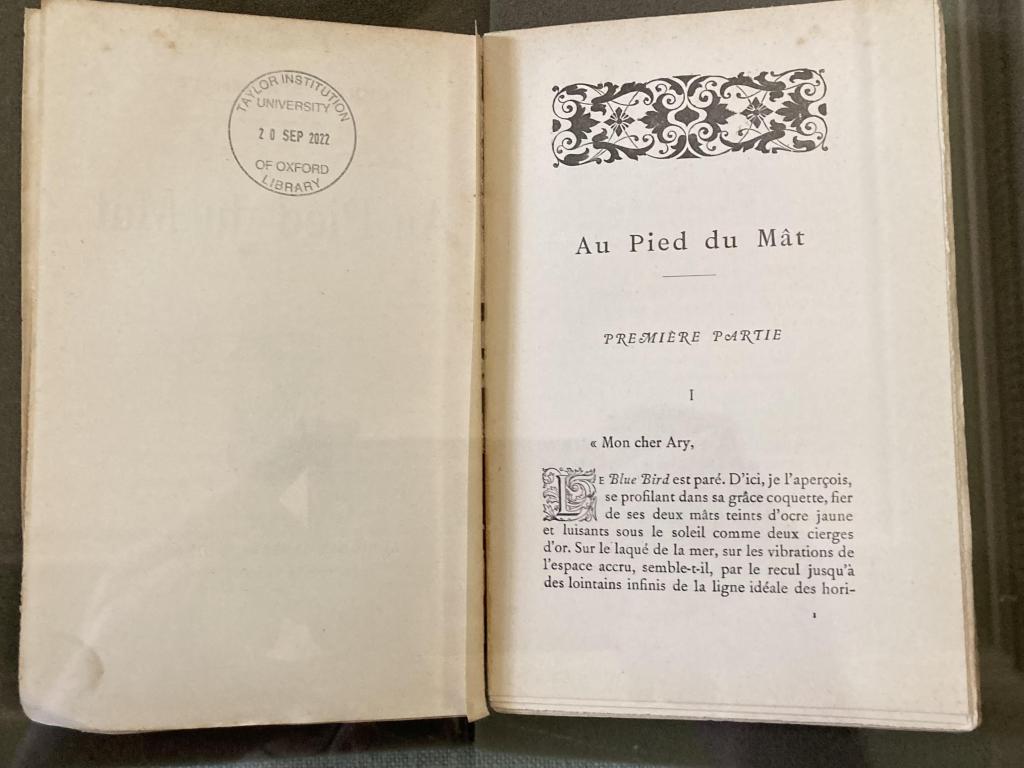

Georges de Peyrebrune, Woman, Writer, Feminist, was an exhibition held at the Taylor Institution (Voltaire Room) from 12th October until 26th October. It showcased the Taylor’s unique collection of Georges de Peyrebrune’s works. On the 20th of October, Jean-Paul Socard, St Edmund’s Hall alumnus and expert on Peyrebrune’s works, gave a fascinating talk at the Taylor Institution on this forgotten French feminist writer. He also brought objects from his personal collection ranging from letters, articles about Peyrebrune to exceptional first editions of her works.

I came across Georges de Peyrebrune during the first year of my DPhil as I was looking for women writers in contact with naturalist literary circles in end-of-nineteenth-century France. I became fascinated with Peyrebrune, born in the Périgord, who became very successful in Paris in the 1880s and 1890s with her political and feminist novels. Despite her literary success, Georges de Peyrebrune struggled all her life with money and died in poverty, in 1917. Because of Peyrebrune having been forgotten and erased from the French literary canon, her works are particularly difficult to access. The Taylor Institution’s collection of her works is therefore unique in the United Kingdom as it holds several first editions of Peyrebrune’s works, as well as a wide range of digitalized ones. I organised this exhibition to make Oxford students and staff aware of this exceptional collection, but also to encourage them to (re)discover this captivating figure of the French Belle Epoque.

In his talk, Jean-Paul Socard told us about Peyrebrune’s life and work, her struggle to become a respected author, but also about her political engagement – she took the defence of the falsely accused Dreyfus during the Dreyfus affair – and her feminist values. Georges de Peyrebrune’s trajectory as a woman and a writer tells us a lot about a society which denied women intelligence and creativity. Peyrebrune reclaimed the negatively connotated term ‘Bas-bleu’ (derived from the English ‘blue stockings’) to designate herself and her peers. In a comic text, play Jupiter et les Bas-bleu published in 1894, she even stages Emile Zola, one of the main literary figures of the time, under the traits of Jupiter, posing as a judge putting her contemporaries on trial to mock men’s arguments for the exclusion of women in public life.

Peyrebrune’s literary career also gives us a glimpse of feminine and feminist literary networks of the Belle Epoque. Peyrebrune’s correspondence show that she stood in solidarity with other women writers and tried to build a literary network made of women. This work towards promoting women’s writing led Georges de Peyrebrune to be part of the first jury of the Prix de la Vie Heureuse. This prize was launched in 1904 by women intellectuals and writers who were tired to see that the prestigious Prix Goncourt was year after year given to a man, despite women’s serious contributions to the contemporary literary market. This prize became the Femina prize in 1917 and is still awarded today.

Most importantly, I believe Peyrebrune’s works should be rediscovered and even integrated in our French canon because of her feminist engagement. Her concern with sexual violence, for instance, makes her fiction strikingly relevant for readers today. In Le Roman d’un Bas-Bleu (The novel of a Blue-Stocking, 1892), she tells the destiny of a young writer who falls into despair as she refuses to compromise her self-worth for literary success. This novel poignantly reflects the debates started by the #MeToo movement which unveiled the harassment and abuse faced by women, particularly in their professional lives. Already in the nineteenth century, Georges de Peyrebrune denounced this harassment and how it kept women from accessing the public sphere as equals to men. Her message strongly resonates with contemporary debates.

This exhibition was a tribute to her work and feminist engagement. In my work, I seek to demonstrate how women writers at the end of the nineteenth century engaged with contemporary debates on femininity and mental health and did not let male voices silence their own. It is sometimes hard to access their works and archives (letters, personal notes, or other biographical materials) because they have been erased from our canon. The Taylor Institution acquiring several of Peyrebrune’s works (both physical and digital) is of a great help for my work and, I hope, the beginning of a renewed interest in this woman, writer, and feminist.